In recent months, wheat markets have stabilized, contrasting the unprecedented volatility following war, drought, and economic uncertainty that has defined markets over the last few years. After dipping to price levels not seen since 2020 earlier this year, world FOB values have recovered slightly, clustering near $250/MT.

We have previously looked at long-term trends in world wheat markets, analyzed price movements, and highlighted key opportunities for U.S. wheat in this forum. However, as the market stabilizes and import prices become more competitive for wheat customers, one key segment of the value chain has not reaped the benefits.

In today’s analysis, we will examine current price trends from the U.S. farmer perspective, considering factors that affect their profitability and planting decisions — decisions crucial for their families’ well-being and for a hungry world.

Mounting Macroeconomic Pressure

Mounting macroeconomic pressures in the U.S. have impacted businesses industry-wide, forcing large multinational agribusinesses like Cargill and John Deere to implement layoffs. Persistent inflation diminishes domestic purchasing power across the supply chain, while a strong U.S. dollar exerts downward pressure on commodity prices. Concurrently, as the U.S. Federal Reserve attempted to control inflation, rising interest rates increased both the frequency and cost of borrowing.

As economic conditions deteriorate, a recent study by Rabobank indicated that, while many farms are projected to remain financially stable through 2024, farm financial health has been declining since 2021. This trend is reflected in key indicators such as liquidity, profitability, and solvency. Supporting their findings, the USDA’s 2024 Farm Sector Income Forecast, released on Dec. 3, estimated that working capital, a common measure of liquidity, is expected to decrease 9.1% from 2023. Although, solvency measures such as debt-to-asset ratios are expected to improve slightly, overall farm sector debt is expected to increase 4.5% to a record $542.5 billion. As farm profitability metrics decline, loan volumes rise. According to Rabobank, in the first quarter of 2024, loan volumes increased by 14%, marking the sharpest uptick since the 1980s, while the USDA income forecast sees interest expenses increasing 4% from last year.

Given increased debt and a weakening financial position, farmers generally do not change crop production decisions directly; however, a continued trend could suggest a coming agricultural industry recession, potentially altering the current size and makeup of farms moving forward.

The Stickiness Factor

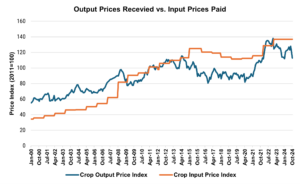

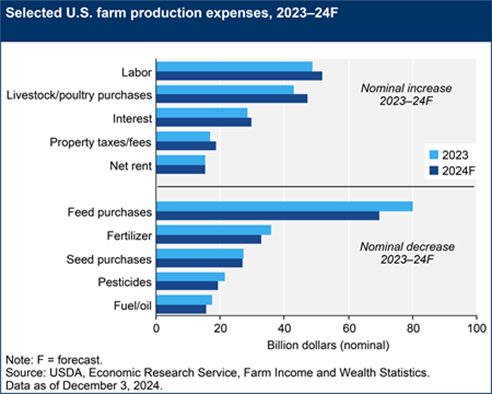

Looking at farm specific inputs, input prices lag behind falling output prices, eroding farmers’ profitability. Operating expenses for fertilizer, seed, chemicals, and fuel have decreased slightly in 2024 but remain elevated compared to pre-war levels, staying “sticky” even as commodity prices drop.

USDA estimates that fertilizer expenses in 2023 were 11% above pre-war levels. Crop protection products and fuel expenses are 8% and 11.3% higher respectively than pre-war figures. Seed costs are the “stickiest,” remaining 21% above pre-war levels. Meanwhile, other expenses, including labor, borrowing costs, and property taxes, have increased from last year.

These sticky costs have led farmers to adjust expenditure on some inputs such as machinery and fertilizer. However, not all inputs can be cut equally. Seed and crop protection products have more “inelastic” demand, meaning that volume tends to not fluctuate with price. These price discrepancies cut directly into the producer’s margin.

Furthermore, farmers must make planting and input purchasing decisions months before harvest, creating price risk and a lag between input use and commodity prices.

The Profitability Conundrum

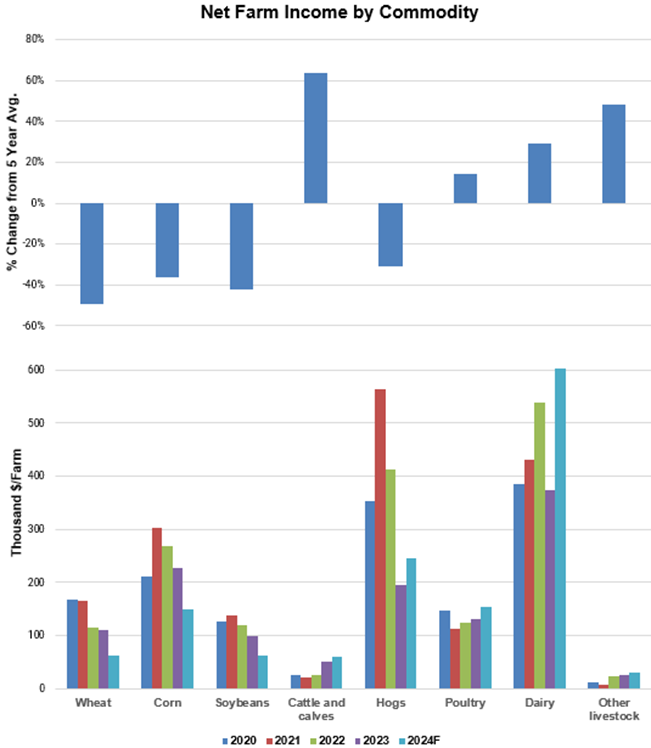

The total farm sector income is projected to decline more slowly in 2024 than in 2023, following record highs in 2022. The USDA estimates net farm income at $140.7 billion, down 4% from the previous year and 19% from the 2022 peak of $181.9 billion. By commodity, farm income from grains and oilseeds trends lower compared to producers in animal production or specialty crops.

Further, the recent decrease in farm income is twofold. Although increased U.S. farm output in 2024 boosts income, the larger volume was insufficient to offset the impact of lower commodity prices.

In another period of lower commodity prices, “sticky” input costs, and a weak macroeconomic environment, producers’ margins continue to be squeezed, creating a nationwide profitability conundrum. The results are not clear but specifically, income shortfall of U.S. wheat production relative to other, more profitable crops has been a factor in the well-documented decline in wheat planted area.

As we were working on this cost-price challenge, a tentative agreement in the U.S. Congress on economic assistance and disaster relief for growers across the country was forged. Political divisions now appear to have scuttled that agreement leaving more uncertainty. Such support would have been welcome not only to farmers, but also to their customers who value and rely on them for high-quality products.

Amidst the uncertainty, farmers will continue doing what they have always done: persevere whatever comes.