Kitchen table math can be a chore this time of year, as U.S. wheat farmers shovel their crop production costs into calculators, hoping the numbers they scoop out next year will be magically heavier than those they tossed in this year.

But here’s a secret about the math of farming: it isn’t really magic.

“There’s a lot of work and a lot of luck involved in making a profit in our business,” is how U.S. Wheat Associates Chairman Michael Peters put it. “The numbers are rarely where you need them to be or where you want them to be.”

An important thing for customers of U.S. wheat to keep in mind is that input costs and the prices farmers receive for their crops each year go a long way toward determining which crops farmers choose to plant the next year.

“The goals of a U.S. farmer are to help feed the world and to also feed our own families,” said Peters, who grows wheat and raises beef cattle in Oklahoma. “We make a lot of decisions each year based on market conditions and expenses. And those are two things that tend to go up and down a lot. They are never stagnant.”

Farming’s ‘Reality’ Math

Although 2023 input costs have been, in general, mostly lower than the costs wheat farmers endured a year ago, a profitable 2024 is far from guaranteed. While crop production expenses have fallen a bit and are expected to remain lower compared to last year’s cycle, commodity prices – including the prices paid to farmers for their wheat – are also forecasted to be lower.

That’s farming’s reality math.

Wheat prices have declined about 27% since the start of 2023, according to Rabobank, and now trades at levels well below those seen before the war in Ukraine began in early 2022. Lower wheat prices are attributed mostly to strong Russian wheat production and a pattern of opportunistic import purchases.

Despite lower prices, farmers appear committed to putting wheat in the ground. In its most recent forecast, USDA put the planted area for wheat that will be harvested in 2024 at 48 million acres, which would be down 1.2 million acres from the 49.6 million acres in 2023 but above the 5-year average of 46.4 million acres.

Better and Worse

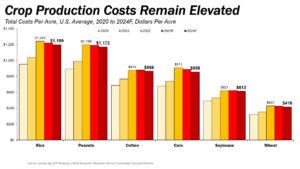

In mid-2024, USDA’s Economic Research Service released a cost-of-production forecast for major field crops that included updated projections for 2023 costs and the first look at estimated production expenses for 2024. Notably, input costs for the 2024 growing season are expected to be the third-highest all-time, behind only 2022’s record-high and 2023’s second-all-time high.

The slight downward trend in input costs does hold some promise, farmers say.

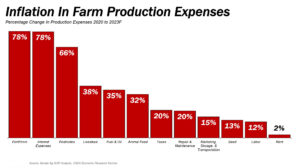

“Chemical prices are probably half of what they were and fertilizer prices are down 30% to 40%, maybe 50% in some cases, depending on the product,” said North Dakota wheat farmer and USW Secretary-Treasurer Jim Pellman. “Fuel prices have moderated a little bit. So generally, major inputs have reduced the last couple of years. But at the same time, you’re seeing lower prices. The best-case scenario for a farmer is low inputs and high grain prices. The worst-case scenario is high inputs and low prices. We are not seeing either of those right now. So it could be better, but it could be worse.”

Some Hope for Wheat Growers?

While input costs remain relatively high, according to USDA, among the major field crops, the cost-of-production for wheat is forecast to be the lowest at $416 per acre, down 2.3%. Yet challenges remain.

“Describing the last three years of global agricultural commodity prices as volatile is an understatement,” said Carlos Mera, head of agri-commodities at Rabobank. “Producers are still grappling with the after-effects of war, adverse weather, high farm input inflation and weak consumer demand, but eyeing 2024 as the return to a semblance of normality.”

Winners and Losers

Rabobank predicts that prices wheat will remain subject to weather and export-related uncertainty, as it has for several years now.

“Winners and losers will emerge as agricultural commodities go through different points of the cycle next year,” Mera said.

For wheat, Rabobank expects another supply deficit in the global market. There will be little relief from the Southern Hemisphere crops in the coming months, with both Argentina and Australia underperforming. El Niño could leave fields in Australia with little moisture ahead of the 2024 planting season, according to Rabobank.

U.S. wheat farmers have been through these kinds of up-and-down supply and demand cycles before. They do their best to make planting decisions based on the best information they have in the fall and spring each year.

“The difficult part for a farmer is that we have to make our planting plans far in advance, well before we know exactly what the market is going to be like at harvest time,” explained Pellman. “We can’t predict the weather, either. That’s our world. But, we are still able to produce a high-quality crop every year.”