By Steve Mercer, USW Vice President of Communications

Wheat farmers in post-World War II United States were producing more wheat than ever before. So, to improve marketing opportunities, they organized and reached out to the U.S. Department of Agriculture for help. These visionary state wheat leaders ultimately formed two regional organizations to coordinate export market development: Western Wheat Associates and Great Plains Wheat Market Development Association.

In the first of a series on the “Legacy of Commitment,” Wheat Letter offers historical perspective on the founding of Western Wheat Associates and its activities. Future posts will focus on Great Plains Wheat, and how the two organizations evolved together into one national export market development organization.

Homesteaders in the semi-arid region of eastern Washington state and Oregon slowly started growing wheat to supply flour for mining camps in the mid-1800s. These growers soon found a route to new overseas markets via the Snake and Columbia river system, though not initially to Pacific rim countries. Early histories of the region’s grain trade include news of a full cargo of wheat loaded in Portland, Ore., on a British vessel bound for Liverpool in 1868.

That trade with Britain and domestic West Coast markets continued to grow into the 20th Century. The first indication of Asian market trade dates to 1906 when Japan’s Masuda Flour Milling Co. imported flour from Centennial Mills in Spokane, Wash.

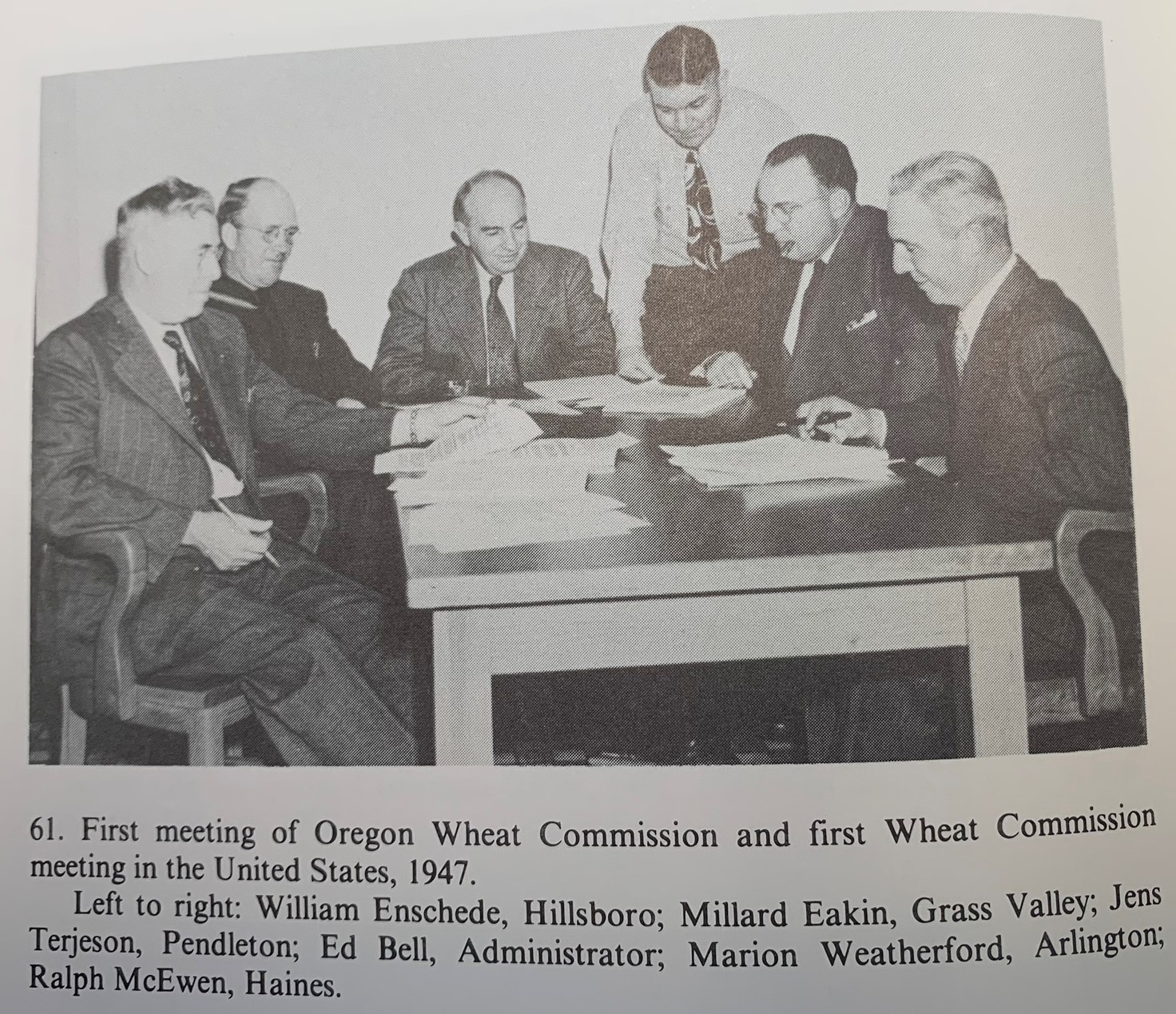

The effort to build greater demand for wheat at home and abroad took wing in 1926 at a meeting hosted by the Oregon Agricultural College extension service in Moro, Ore., where wheat farmers decided to form the Eastern Oregon Wheat League. In 1945, that organization asked its state government to create a wheat “commission” with the power to “tax” each bushel of wheat entering commercial channels to fund wheat promotional activities. The Oregon Wheat Commission (OWC) was established in 1947 (see photo below) and in 1949 sent representatives to Japan who reported “great opportunities for trade,” depending on the ability of Pacific Northwest (PNW) farmers “to establish a productive relationship with flour millers and provide high-quality wheat at a competitive price.”

In the book “Kernels and Chaff; A History of Wheat Market Development,” Marx Koehnke wrote that “these Oregonians had established a unique approach to self-help… It was a revolutionary and challenging idea” that “in turn resulted in other states exploring and adopting similar plans.”

In the PNW, Washington state and Idaho soon established their own state commissions and began cooperating with the OWC to promote the region’s soft white (SW) wheat in overseas markets. Surplus U.S. production was poised to meet growing demand for food in a post-war world. Farmers took a key step in 1956 when the Oregon Wheat Growers League opened the first U.S. wheat office in Tokyo. Commissions from Washington state established relationships with India and Pakistan, joined by agreements with the Nebraska Wheat Growers Association and the USDA’s Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS).

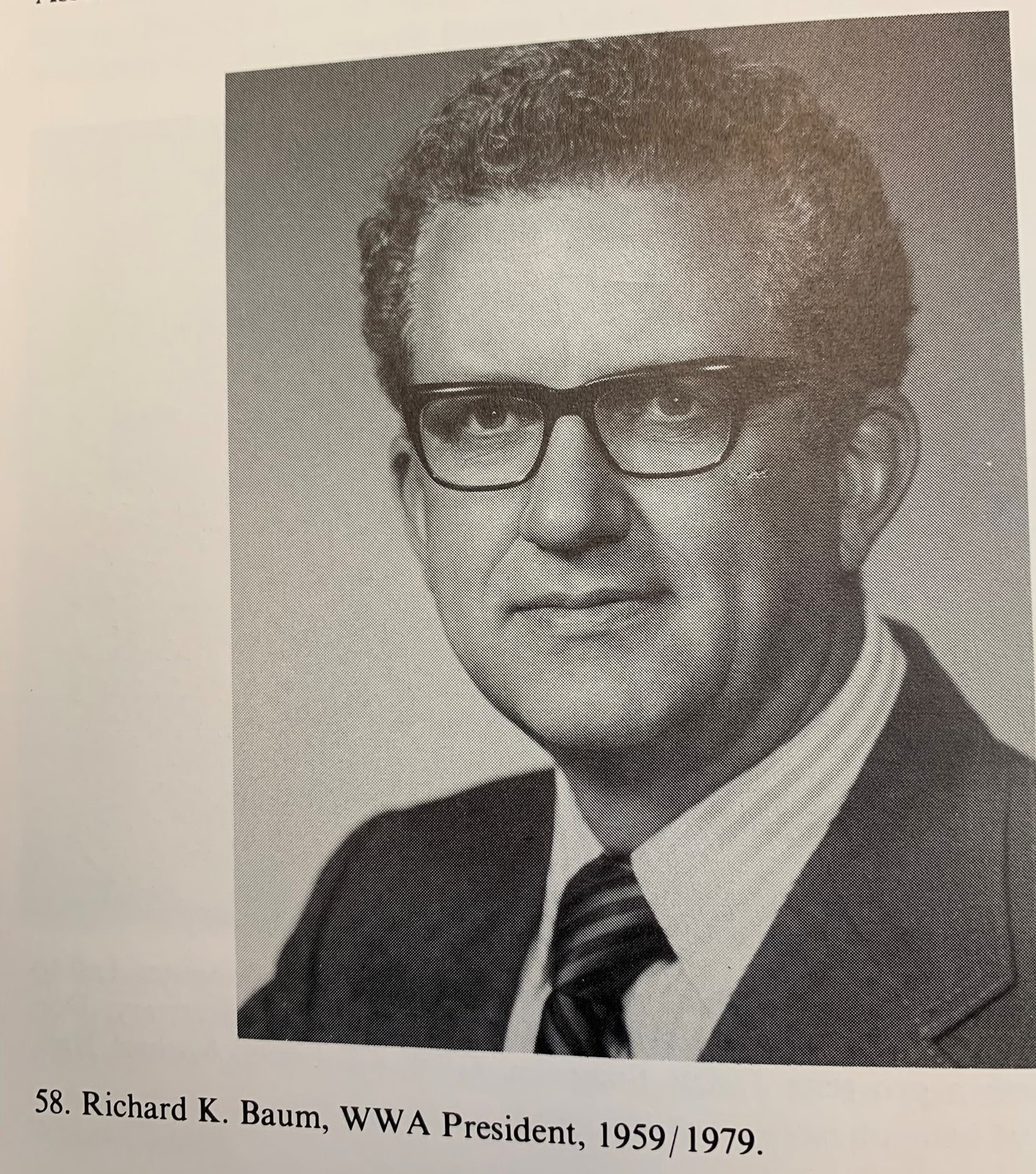

According to “Western Wheat Associates, The First Twenty Years,” by Richard K. Baum, PNW farm leaders met with farmers from the Plains in early 1959 to discuss establishing working relationships between the regions and export promotion plans. With Plains growers indicating they planned to promote hard red winter (HRW) wheat in “Far East and South Asia markets, if permitted,” the PNW state commissions decided to unify export activities.

In Pendleton, Ore., on April 23, 1959, Western Wheat Associates, U.S.A., Inc., was created. Officers were elected and a board of farmer directors from the PNW states was appointed. Baum was selected to serve as executive vice president, a position later changed to president that he would hold until U.S. Wheat Associates (USW) was formed in 1980. The organization’s headquarters office was established in Portland.

A Different World

In many ways, Western Wheat Associates (WWA) operated for 20 years in a global wheat market and trade policy environment that few in the trade today would recognize. In 1954, for example, the U.S. federal government established Public Law (PL) 480, allowing food-deficient countries to pay for U.S. food imports in their own currencies instead of in U.S. dollars. The law helped the United States create the environment for exports of surplus agricultural products while supporting so-called “friendly” nations as the Cold War intensified.

Under the early PL480 program, the government purchased U.S. wheat and sold it to designated countries including India, Pakistan and South Korea. WWA received matching funds from the PL480 program to help facilitate the transactions, acting in a sense as the U.S. government’s service representative in in those countries.

Wheat supply and price management ruled both international and domestic U.S. wheat policies during WWA’s existence. As early as 1933, wheat exporting and importing countries formed an “International Wheat Agreement” to help “adjust the supply of wheat to effective world demand and eliminate the abnormal surpluses which have been depressing the wheat market” and to stabilize prices. Similar price and supply agreements continued well into the 1990s that were, in effect, efforts to control the international wheat market.

Through the 1960s and into the early 1970s, U.S. policy supported international agreements to export wheat at a “world price” but also attempted to protect farmers and the grain trade from rapid changes in prices. Production quotas were established. Subsidies incentivized farmers not to plant too much wheat or other crops or paid farmers when cash prices fell below minimum levels. Export subsidies were established to allow grain traders to sell at agreed-to world prices with minimal risk.

Even in importing countries that were not designated as PL480 markets, which WWA and the trade referred to as “cash” markets, government agencies were charged with importing food commodities, a situation that put significant weight in the transaction on the per-metric-ton price of U.S. wheat. Much of the early WWA development work in PL480 and “cash” markets focused on introducing wheat foods to primarily rice-eating cultures.

Building the Case for U.S. Wheat

Sales of U.S. wheat continued to increase as WWA expanded its staff and activities. Eventually, wheat farmer organizations from Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, Wyoming, Colorado and Texas became members of WWA or contracted with WWA to represent their wheat supplies. Working under contract with the U.S. government and Great Plains Wheat (GPW), WWA developed markets in Asia for the SW class grown in the PNW, for hard red spring (HRS) grown in Montana and North Dakota, and HRW grown in the Plains states. Great Plains Wheat (GPW) had a similar cooperator relationship with USDA as WWA and its state wheat organization members, representing their interests in Latin America, Europe, the Middle East and Africa.

WWA worked from offices in Tokyo, Delhi, Karachi, Manila and eventually Taipei, Singapore and Seoul. Limited records of specific activities make it difficult to list the many market development activities implemented by WWA over the years. In addition to introducing wheat foods, more familiar trade activities included: participation in trade shows; sending trade delegations of farmers and government representatives to overseas markets to promote U.S. wheat and to evaluate market potential; and bringing buyers and flour millers to the PNW and Northern Plains.

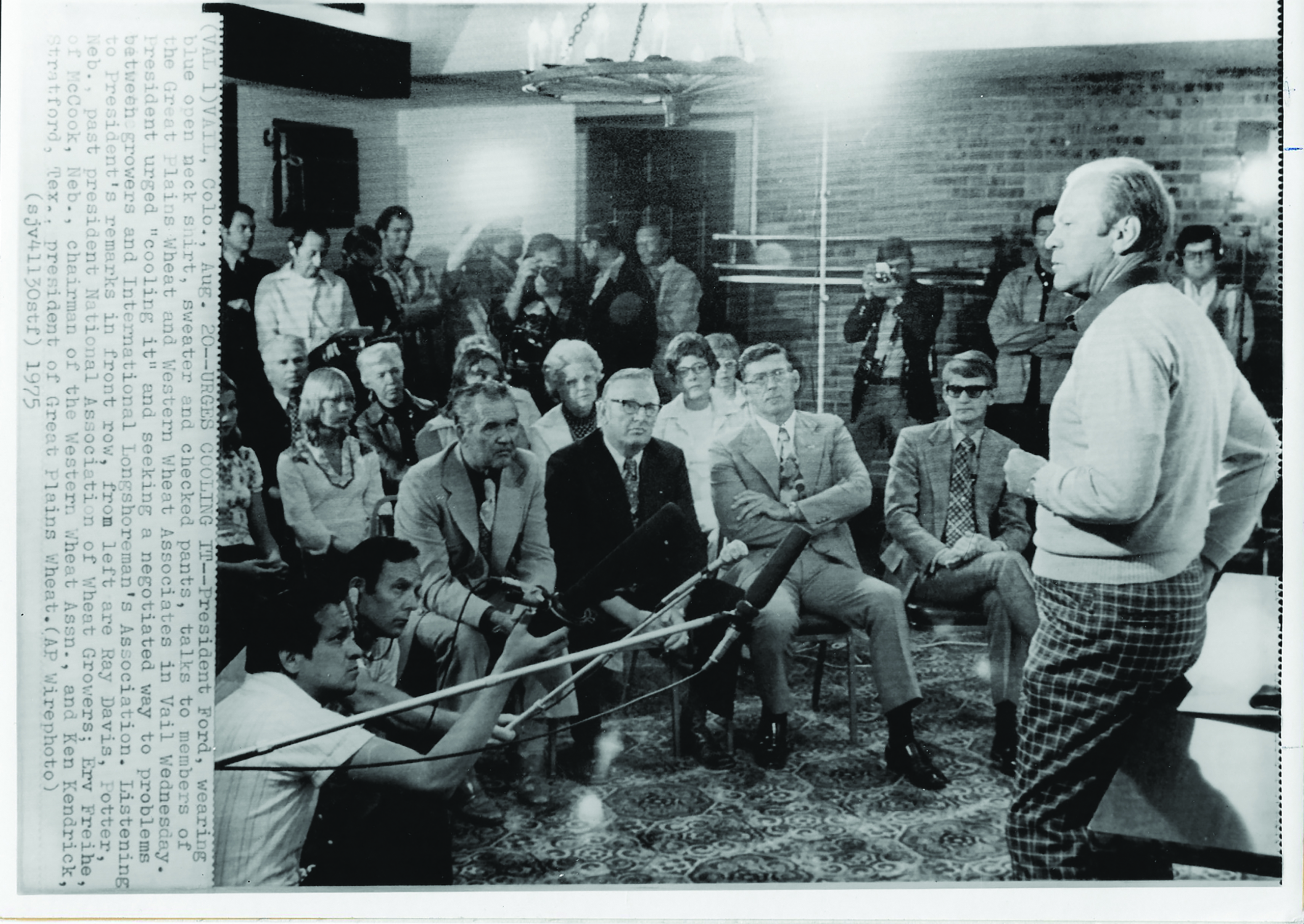

The work certainly had unique challenges that WWA had to maneuver. For example, the organization and its state members worked with the U.S. government to improve grade standards for U.S. wheat in the 1960s. Information from customers, especially from Japan, about high levels of sprout damage were shared with growers, wheat breeders and other researchers. WWA even took dock worker union leaders to Asian markets to demonstrate the broad economic effects of U.S. wheat trade. All these efforts and more were focused not only on building demand, but also on building a case that customers could count on the U.S. wheat export supply system.

It was government intervention, however good intentioned, that greatly endangered the reliable reputation of the United States as a grain supplier. In 1972, the Soviet Union took advantage of U.S. government guarantees of low wheat export prices and a politically motivated offer of credit guarantees to quickly purchase massive volumes of U.S. wheat. The Soviet purchases coincided with low production in other exporting countries and created a supply shock that literally doubled world wheat prices in just a few weeks. Established customers such as Japan were unprepared for the supply and price problems that followed. Interventions continued in the 1970s including an embargo on U.S. soybean exports to Japan and the U.S. grain export embargo following the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan in 1980.

Yet, the farmers who established WWA and the people the organization hired to represent their interests persevered. The legacy they, and the people who started and ran GPW, created lived on through WWA’s existence and continues even today through U.S. Wheat Associates and its 17 state wheat commission members and board of directors.

WWA’s Richard K. Baum captured the enduring spirit of the organization as he wrote to his board about “The First Twenty Years” of WWA.

“It has been my privilege, and an unusual one at that, to have served throughout this entire period as chief executive officer of Western Wheat Associates. Many of our staff people have also served for 18 and 19 years. Our personnel record is a stable one. Our employees, particularly those overseas, feel they are a part of a close-knit family and work as hard for you wheat producers as they would if this were their own business.”

“Those of us who have worked with you [farmers] believe fully in the goal of obtaining a fair return to the farmer for his investment, management and labor. We admire his dedication and unselfish service. We believe your leadership as evidenced by these past board Chairman have been outstanding.”

# # #

Sources for this post include:

- Richard K. Baum, Western Wheat Associates, U.S.A., Inc., The First Twenty Years, 1959 – 1979 (self-published, 1979).

- Marx Koehnke, Kernels and Chaff, A History of Wheat Marketing Development (self-published, 1986).

- Donald W. Meinig, “Wheat Sacks Out to Sea, The Early Export Trade from the Walla Walla County,” Pacific Northwest Quarterly,” University of Washington, January 1954.

- Joseph Albright, “The Full Story of How America Got Burned and the Russians Got Bread,” New York Times, Nov. 25, 1973.

- William F. Schillinger and Robert I. Papendick, “Then and Now: 125 Years of Dryland Farming in the Inland Pacific Northwest,” Agronomy Journal, 2008.

- Washington Grain Commission

- Oregon Wheat Commission

- Idaho Wheat Commission

- Montana Wheat and Barley Committee

- North Dakota Wheat Commission

Read other stories in this series:

Great Plains Wheat Focused on Improving Quality and HRW Markets

Evolution of a Public-Private Partnership

The U.S. Wheat Export Public-Private Partnership Today

NAWG, USW Lead the Way Through Issues Affecting Wheat Farmers