By Steve Mercer, USW Vice President of Communications

Wheat farmers in post-World War II United States were producing more wheat than ever before. So, to improve marketing opportunities, they organized and reached out to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) for help. These visionary state wheat leaders ultimately formed two regional organizations to coordinate export market development: Western Wheat Associates and Great Plains Wheat Market Development Association.

In the second of a series on the “Legacy of Commitment,” Wheat Letter offers historical perspective on the founding of Great Plains Wheat and its activities. Additional stories will review how Western Wheat Associates and Great Plains Wheat evolved together into one national export market development organization.

Wheat production on the Great Plains took root in the late-1860s with Mennonite farmers emigrating to the heartland of the United States to escape religious persecution in the Crimea. They planted the hardy, drought-resistant winter wheat seed they carried with them to Kansas and Nebraska, and “Turkey Red” would become the parent for most hard red winter (HRW) wheat varieties well into the 20th Century.

After surviving the infamous “Dust Bowl” of the 1930s, inconsistent quality and yields, and the challenges of a world war, Plains farmers pooled their time, talent and treasure to improve their industry. They established the Western Kansas Development Association in 1947 with a “Farm and Wheat Division” (which later became the Kansas Association of Wheat Growers). Three years later, with knowledge of a similar effort by farmers in Oregon, Nebraska formed the Nebraska Wheat Research Foundation. It was funded by about 300 members who agreed to authorize local elevators to collect one-half of one cent per bushel that would be spent to “help stabilize wheat production.”

Improved agronomics and varieties followed but added to a burdensome wheat surplus in the 1950s. This caught the attention of the U.S. government, which created federally managed grain reserves to help increase cash prices. In 1954, Public Law (PL) 480 was implemented to help expand exports of surplus agricultural products while supporting so-called “friendly” nations as the Cold War intensified.

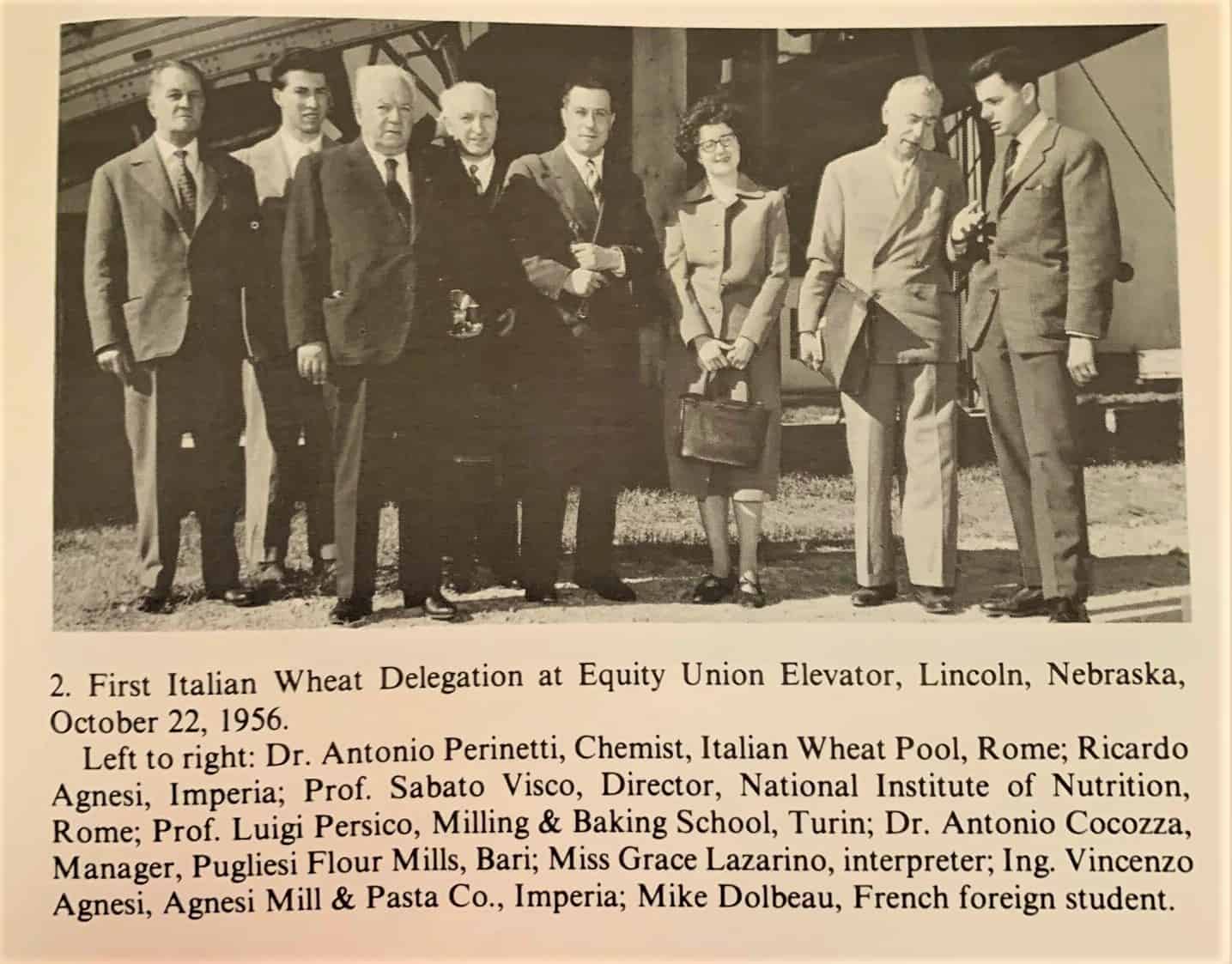

Yet “there had been no effort to promote wheat exports by growers,” according to Marx Koehnke, author of Kernels and Chaff: A History of Wheat Market Development. The Nebraska Wheat Commission, formed in 1955, changed that as the first Plains state organization to sign an agreement with USDA’s Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS) to co-fund and implement export market development activities. They sponsored two teams of government buyers and milling industry representatives from Italy in 1956 and Greece in 1957, who observed wheat production, handling, milling and baking in Nebraska, Kansas and Oklahoma. The resulting purchases of U.S. wheat encouraged signing of the first regional agreement between Plains farm organizations and FAS to promote U.S. wheat exports in Europe and Latin America.

A two-month long survey trip in 1957 to evaluate the market opportunities in Europe by representatives from Nebraska, the newly formed Kansas Wheat Commission and FAS proved to be a pivotal activity. The insight into customer needs gained from that trip formed a basis for export development strategies that U.S. Wheat Associates (USW) still emphasizes more than 60 years later.

In its report, the survey team made these recommendations:

- Establish a permanent presence in the market (the Nebraska and Kansas wheat commissions opened a U.S. wheat export office in Rotterdam, The Netherlands, in January 1958);

- Discourage production of “low grade” wheat worldwide;

- Establish tighter grade specifications for U.S. wheat exports;

- Make information about the milling and baking quality of wheat in each cargo available to the buyers before arrival.

A survey of South American markets added the recommendation that grower organizations should help wheat buyers, most of whom were government officials, write specifications for U.S. wheat to ensure they receive the best quality at the best value.

Something for Themselves

According to Kernels and Chaff, the Nebraska wheat organizations first discussed a regional organization in 1958. Their contacts at FAS recommended that an organization of Plains states must also promote U.S. hard red spring wheat (HRS). That is why North Dakota farmers were represented at a meeting in Dodge City, Kan., where influential Kansas farmer Herbert Clutter advocated a regional organization so “growers can be in a position to do something for themselves instead of expecting others to do something for them.”

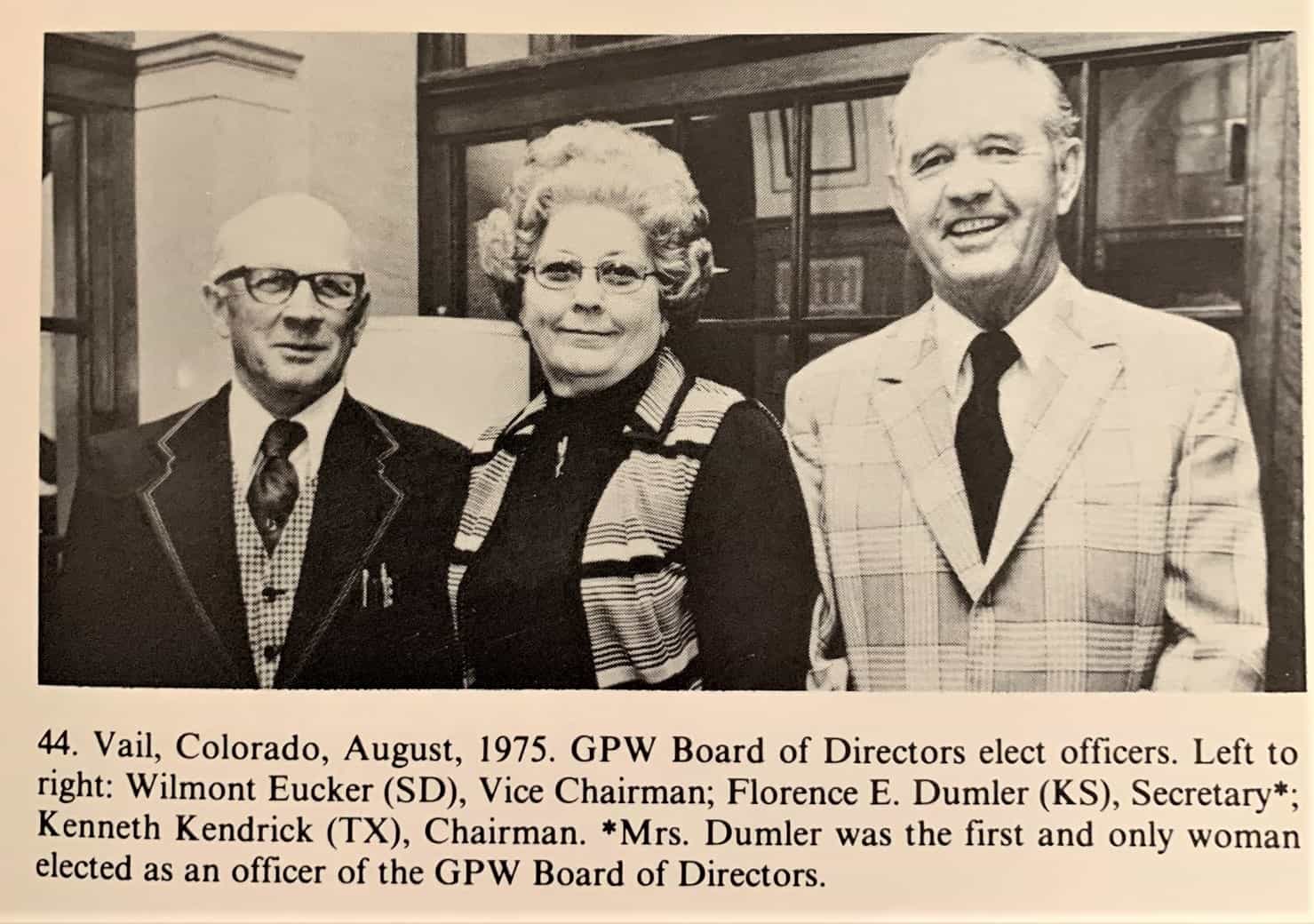

With a goal to add more resources from more farmers to export market development, Plains state wheat leaders drafted bylaws and proposed a name for a regional organization. On Dec. 15, 1958, state commissions from Nebraska, Kansas and Colorado made the commitment to form and fund Great Plains Wheat Marketing Development Association, Inc., later shortened to Great Plains Wheat, Inc. (GPW). Over the next 10 years, state commissions from Oklahoma, Texas, North Dakota, South Dakota and Minnesota would join GPW.

The new organization took over already established export promotion offices in Rotterdam and Lima, Peru. A prior agreement with Pacific Northwest (PNW) states Oregon and Washington to promote HRW in Asian markets transferred to Western Wheat Associates (WWA) after it was established in 1959. Garden City, Kan., was selected as the first GPW headquarters office and the organization integrated into a Washington, D.C., office set up by the Nebraska Wheat Growers Association in 1958 to maintain coordinate contact with FAS officials.

Those officials had a big influence on the expansion of GPW’s activities in the early years. With foreign currency funds growing from PL480 sales, FAS strongly encouraged GPW to study broader opportunities in South America, Central America, the Caribbean and in Africa. Of course, the U.S. government wanted to move wheat from reserve stocks into PL480 export markets and that required trade servicing and local support that GPW provided, but FAS also supported GPW’s export development efforts in commercial markets.

Better Quality Needed

No matter where U.S. HRW was being promoted, the issue of quality was a significant constraint. Because U.S. wheat grade standards at the time included much more tolerance for defects, overseas customers had legitimate concerns about imported U.S. supplies. Export supplies often came out of long-term storage and limited oversight of grain inspectors licensed by USDA occasionally created complaints about short sales and out-of-specification cargos.

Based on previous survey work, GPW started collecting samples of U.S. wheat export cargos in Europe and established a wheat and flour testing site in Lima. This yielded information GPW could use to inform grain handlers and government reserve managers about problems. The organization also advocated for expanded storage at U.S. Gulf elevators and for limiting the export of government owned reserve stock wheat to PL480 markets. Progress on such changes was slow, however, and alternative exporters like the Canadian Wheat Board aggressively touted quality relative to U.S. wheat. The general reputation for poor quality persisted. More work needed to be done.

GPW turned to James Doty, one of GPW’s cereal consultants and head of Doty Laboratories in Kansas City, Mo., to start conducting wheat quality analysis on HRW export supplies as the laboratory had been doing for U.S. flour mills. The “Doty Report” on the 1960 HRW crop quality was the first in an annual effort to inform overseas buyers, millers and wheat food processors about each year’s crop, which has expanded to include all six U.S. wheat classes in the annual USW Crop Quality Report.

The need to build U.S. wheat into a quality supplier grew with market development to Europe, most of Latin America, the Middle East, North Africa, Nigeria and South Africa, and to Asian markets through contracts with WWA. Herbert Hughes, a dedicated wheat leader from Nebraska, who had served as the first Vice President of GPW, was selected to chair a Grain Standards Committee that identified that crucial changes to U.S. wheat grade standards for HRW and HRS were needed to remain competitive in global markets.

According to Kernels and Chaff, Hughes warned the GPW board and staff in 1963 that improving the official standards “is a fight we cannot…and must not lose.”

GPW promoted the changes to country elevators and their farmer customers, farm organizations, local and state officials, and the grain trade, ultimately winning support from Secretary of Agriculture Orville Freeman. USDA held several hearings on the proposed wheat grade standards. With government export subsidies in place at the time, GPW argued that improved standards would allow the government to adjust the subsidy more accurately.

USDA implemented revised standards in 1964 and adjusted the export subsidy based on grade. The results of a GPW cargo sample study and “reactions of many buyers attested to definite improvement in quality of [exported U.S. wheat]. Compliments were taking the place of complaints…” wrote Koehnke in Kernels and Chaff.

Organization Expands with Export Sales

GPW programs were supporting significant export sales growth in Latin America with offices now added in Bogota, Colombia; Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; and Panama City, Panama In 1965, for example, GPW developed mobile demonstrations and school lunch programs that introduced pasta made from HRW to Brazilian children and families. GPW supported a new baking school in Caracas, Venezuela, and baking trade schools in Colombia. Even in the face of tight specifications enacted among members of the European Economic Community U.S. HRW and HRS continued flowing to the port of Rotterdam to be offloaded to barges and smaller vessels for delivery to European customers. Trade service and technical assistance to developing markets in Africa from a GPW office in Rome initially. Coverage of the Middle East shifted from an office in Beirut, Lebanon, to Cairo, Egypt.

In addition to its local market development support, GPW invested significant effort in general promotion of U.S. HRW and HRS wheat as well as reports back to the farmers and state organizations who directed and co-funded its activities. Brochures, wheat sample cards and a series of films about U.S. wheat were produced. Printed newsletters translated to local languages kept customers informed about U.S. and global wheat market supply and demand factors and a magazine called The Great Plainsmen informed stakeholders at home about progress.

GPW leaders and staff, like their counterparts at WWA, had to operate within the parameters of active government policies and regulations for most of its existence. For example, they fought through the battle of the “Great Grain Robbery” by the Soviet Union and advocated for more transparency and information from USDA to help farmers and their overseas customers that helped lead to weekly commercial sales reports. Their testimony about the critical need for more oversight of export grain inspection informed the Grain Standards Act of 1977 that established the Federal Grain Inspection Service and independent certification of export specifications.

Tried…and Tried Again

With more than 800 names identified in the Kernels and Chaff book index and hundreds of export market development activities in dozens of countries, a complete survey of Great Plains Wheat, Inc., achievement in this space would be almost impossible. Marx Koehnke summarized the experience well.

“Ideas were tried and rejected, and tried again, before success was achieved…Many problems had to be solved; but with a spirit of compromise…and a determination to succeed, a viable organization was formed. By collaboration with its sister WWA and of course with FAS, many successful projects were accomplished.”

###

Sources for this post include:

- Marx Koehnke, Kernels and Chaff, A History of Wheat Marketing Development (self-published, 1986).

- Richard K. Baum, Western Wheat Associates, U.S.A., Inc., The First Twenty Years, 1959 – 1979 (self-published, 1979).

- USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service, News Release, Kansas Wheat History, October 2017.

- Kansas Wheat, Why is Kansas called the Wheat State?, January 22, 2015.

- Rachel Keeley Turner, Nothing But Heart: Celebrating the Life of Herb Clutter, High Plains Journal, March 28, 2016.

- Nebraska Wheat Commission

- Colorado Wheat Administrative Committee

Read other stories in this series:

Western Wheat Associates Develops Asian Markets

Evolution of a Public-Private Partnership

The U.S. Wheat Export Public-Private Partnership Today

NAWG, USW Lead the Way Through Issues Affecting Wheat Farmers