U.S. Contests Chinese Programs that Create Burdensome Wheat Stocks

By Dalton Henry, USW Vice President of Policy

The dispute between the Chinese and U.S. government over wheat production subsidies continues. Late last month, the U.S. government officially challenged China’s purported compliance with the World Trade Organization (WTO) dispute decision that found China spent billions more on agricultural subsidies than their WTO membership allowed. That case was filed in 2016 by the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) to bring the Chinese programs – and their effects on U.S. wheat producers – under control.

The subsidy programs at the heart of the WTO dispute are China’s Minimum Procurement Prices (MPP) guarantee to Chinese producers. This program would be most similar in U.S. farm policy to our Marketing Loan program. But unlike the U.S. version, the MPP is set well above world wheat prices and, as such, creates an artificial incentive for farmers produce more wheat at the expense of a more diverse range of crops. Last year’s MPP for wheat in China was $8.60/bushel; compare that to the U.S. Marketing Loan program at $3.38/bushel and to current U.S. FOB HRW prices at $5.69/bushel.

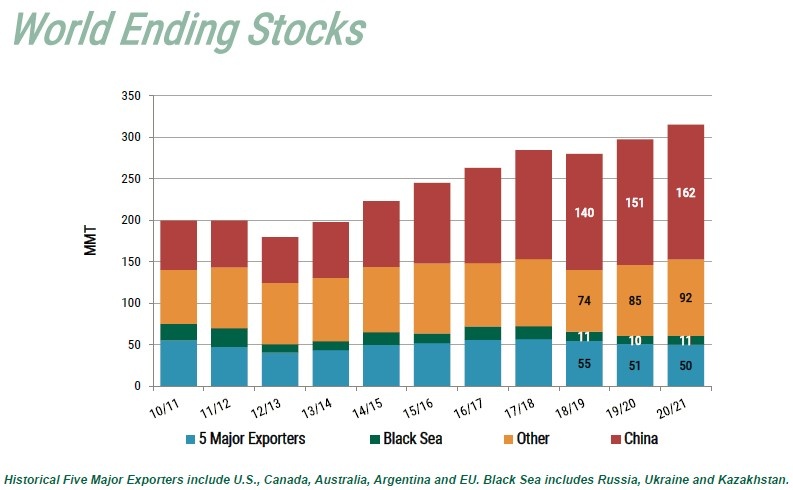

It is no wonder then why Chinese producers have dramatically increased wheat production, up 25 percent from before the policy was put in place. Even more distorting to the global market, much of that production is building stocks rather than being made available at affordable prices to China’s flour millers. Those stocks are projected to end this year at an astounding 162.5 million metric tons (MMT), comprising 52 percent of the entire world’s wheat ending stocks. That volume represents more than an entire year’s consumption in China.

USDA currently predicts that China will hold more than 162 MMT of world wheat stocks at the end of marketing year 2020/21.

The WTO dispute panel recognized this issue in ruling that China had far exceeded its WTO limits on wheat and rice subsidies. In the process of a WTO case, once a ruling has been issued the involved countries agree to a “reasonable period of time” for the policies to be changed and for the offending country to come into compliance. The reasonable period for this case ended last month with China claiming (and the United States disagreeing) that they were in compliance.

A closer look at China’s claims of compliance reveals changes designed only to work on paper. China notified changes to their policy for the coming year that attempt to cap the amount of wheat that the Chinese government will purchase at the MPP. In theory, a laudable effort, but in practice one with little impact, as the cap is set to be at 37 MMT, 40 percent more than their five-year average annual purchases.

As a result, the cap allows China to adjust the math behind calculating their compliance, without actually changing anything about the operation of the program or the unfortunate creation of burdensome stocks. That’s because with a cap set so far above previous purchase amounts, a farmer can approach a flour miller and demand to be paid the MPP. If the miller refuses, the farmer knows the government will purchase the wheat at the inflated MPP. That dynamic allows the distorting effects of the MPP to reach far beyond the actual bushels that the Chinese government purchases.

Market-based reform will have the potential to improve the situation dramatically for Chinese millers, as wheat would be grown and traded according to quality attributes and actual value, rather than that set by government regs. It would also pave the way to reducing the current wheat storage burden – one similar to the situation faced by China’s corn industry just a few years ago. In that instance, program reforms worked and brought stocks to reasonable levels, providing domestic users with more choice and storage capacity.

China’s wheat subsidies and the excess stocks that they produce have been well-documented by U.S. Wheat Associates (USW) and other groups over time, as has the revenue losses they create for U.S. farmers and indeed other farmers around the world.

USW welcomes the continued work on this case by the USTR and hopes to see an end to distortive policies like this that impede our ability to meet global demand for a diverse supply of high-quality wheat.