By Amanda J. Spoo, USW Communications Specialist

Earlier this year, I had the opportunity to travel abroad with some U.S. wheat farmers to learn more about the world wheat market and see how those markets use U.S. wheat. We visited many end-product manufacturers, and as we reviewed their various products, most of our conversations circled back to consumer demand. In the United States, the consumer’s relationship with food is becoming increasingly sophisticated — following new trends and seeking out convenience and information on where it came from. The fuel for this change comes from increasing disposable income, television networks dedicated to food and the growing number of online platforms like food blogs, Pinterest, etc. Although products and taste preferences vary from market to market, the demand for food that is high quality, creative and has a story, is universal.

Here in the United States, I recently had the chance to participate in an event that represents a potentially successful way for the global milling, food ingredient and wheat food industries to tell their stories to consumers. It was the National Festival of Breads, a biennial event held in Manhattan, KS, hosted by the Kansas Wheat Commission and sponsored by King Arthur Flour and Red Star Yeast to showcase bread, U.S. wheat and the art of baking. At the center of the festival on June 17 were eight people selected as finalists in a baking contest, the only U.S. amateur bread-baking competition in the United States. They prepared their original bread recipes live for festival visitors and were judged on creativity, healthfulness and taste to determine a grand prize winner. Judges selected the “Seeded Corn and Onion Bubble Loaf,” made by Ronna Farley of Rockville, MD, as the 2017 National Festival of Breads Champion. The champion recipe and all eight finalists’ recipes are available at https://nationalfestivalofbreads.com.

The festival also featured diverse educational baking demonstrations focused on the versatility of bread, baking tips, convenience and health. The more than 3,000 festival visitors joined in hands-on children’s activities, bread tasting and a trade show featuring the baking industry and a well-rounded look at the U.S. wheat supply chain, including wheat farmers, milling companies, research and extension, and those in product development.

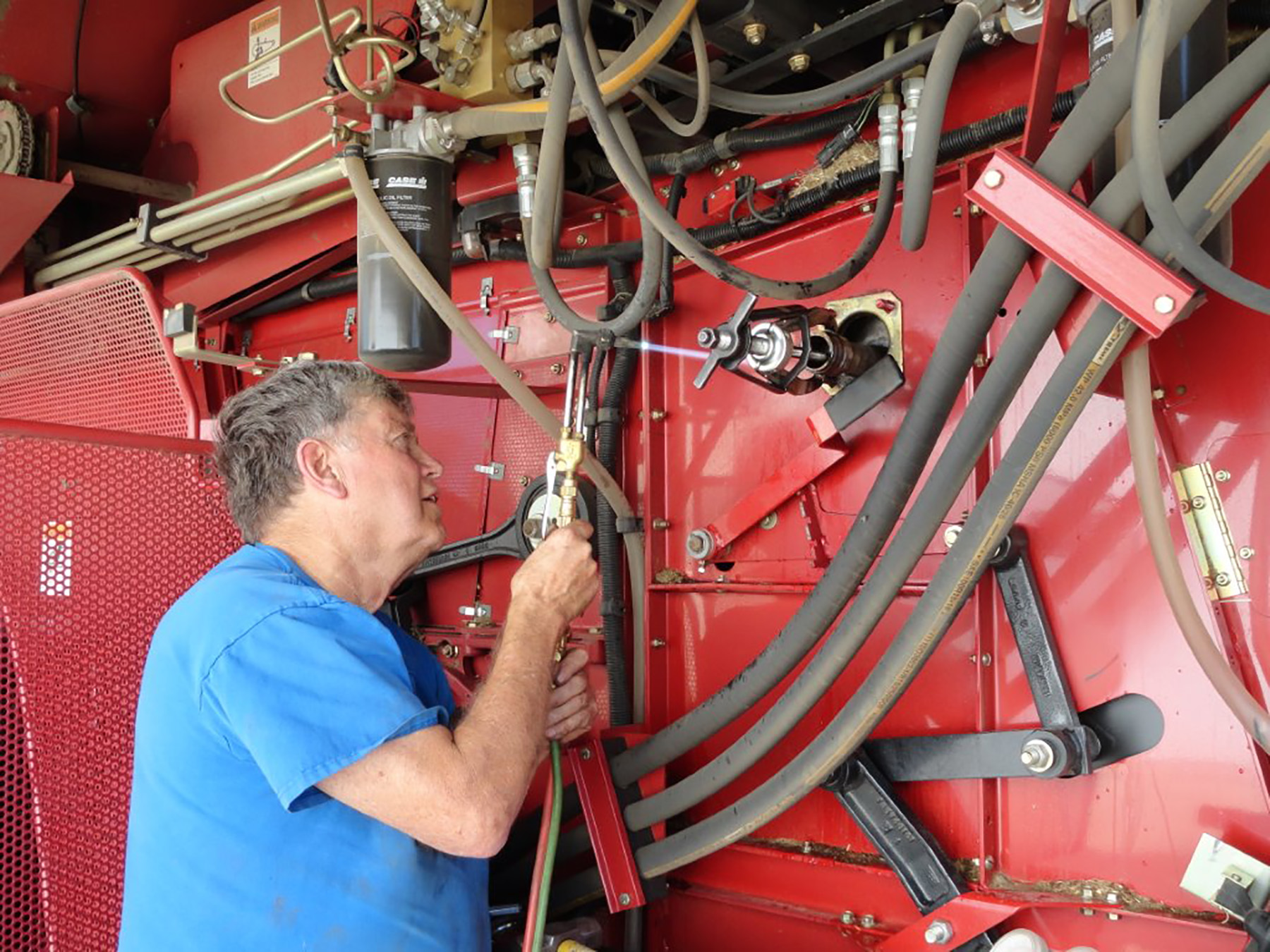

Prior to the festival, the eight finalists also went on a farm-to-fork tour of central Kansas, which included a flour mill, a wheat farm and the Kansas Wheat Innovation Center. On the Kejr family wheat farm, the finalists rode along in the combine to actually participate in the wheat harvest, which one finalist said helped complete the story of the bread into which she put so much of her own care and hard work.

What was advertised as a fun, family-friendly festival for baking really serves as an opportunity to learn about what is important to the consumer and, in return, share information on the role of wheat in their diet — and why bread is so important in so many cultures. My experiences on my trip overseas and at the National Festival of Breads had many parallels, most importantly that listening to the consumer and creating product advantages and stories around their desires is an effective model for success.