By Steve Mercer, USW Vice President of Communications

The aftermath of Hurricane Irma is simply stunning. So many of our Caribbean neighbors are facing so much destruction, including in Cuba where the full fury of Irma raked the northern coastline as a Category 5 hurricane that killed at least 10 people and flooded central Havana.

As I read about the damage in Cuba, I could not help thinking about other hurricanes and their impact on our relationship with the island nation.

In 1998, Hurricane Lily hit Cuba hard, too, putting flour mills offline. The Kansas Wheat Commission responded with a generous offer to donate 20 MT of flour to help Cuban people in need. USW helped coordinate the donation, but it had to be made to Caritas, a CARE affiliate non-governmental organization relief organization, not directly to Cuba, because the U.S. government’s embargo prevented them from sending it directly to Cuba.

We believe that the donation did help open some hearts and minds, and the Trade Sanctions Reform Act (TSRA) of 2001 opened exports of wheat and other U.S. agricultural products to Cuba. Yet, the travel and financing restrictions that remained continued to compound the regulatory difficulties of trading with Cuba.

When another hurricane, Michelle, struck Cuba later in 2001, the U.S. government offered aid. The Cuban government refused that offer, but the gesture helped encourage Alimport, Cuba’s food buying agency, to import its first bulk load of U.S. HRW wheat. According to former USW President Alan Tracy, “Cuba’s flour millers and bakers loved that wheat.”

More and more HRW was imported until the annual volume reached almost 500,000 MT, a substantial portion of Cuba’s annual imports of about 800,000 MT.

In 2005, it was not a hurricane, but rather new regulations implemented by the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) that interrupted this trade. The changes forced Cuba to obtain and present letters of credit from a third-party, foreign bank, and U.S. exporters had to receive payment only from a third-party bank, rather than through direct payment from Alimport. It was an excessive and unnecessary administrative burden that increased Cuba’s cost of buying U.S. wheat. OFAC also modified the definition of “cash in advance” that required payment before a shipment left a U.S. port rather than before the title changed hands at the shipment’s destination. This rule was unique to our exports to Cuba and removed the ability of Alimport officials to inspect U.S. origin cargo before payment.

Alimport slowed and ultimately stopped importing U.S. HRW wheat completely by marketing year 2011/12.

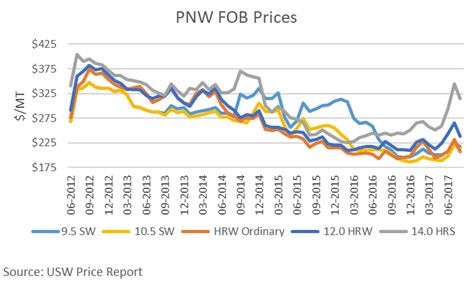

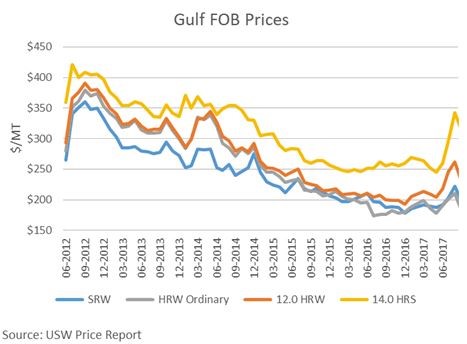

There was renewed hope when the Obama Administration announced its intention to renew and, eventually, re-open diplomatic relations with Cuba and ease some travel restrictions. Several organizations, including USW, formed the United States Agricultural Coalition for Cuba (USACC) to work together toward more open trade. However, the OFAC rules were never reversed and Cuba continued to import all its wheat from Canada and the EU — no doubt at higher freight rates and likely at higher relative FOB costs.

And, sadly, just hours before Irma struck Cuba, the United States officially renewed its embargo for another year, as required under TSRA.

Cuba’s proximity, as well as historical and cultural ties, should make it a natural trading partner for the United States. The U.S. wheat industry supports easing travel restrictions, permanently overturning the 2005 regulatory changes and increasing access to credit and USDA commercial loan programs. However, the larger political implications of the embargo and its negative effects will likely preclude effective competition by U.S. wheat exporters even if these other changes are implemented.

“Aside from hurting the Cuban people, the embargo has only strengthened the Castro brothers’ grip on power and stymied any change for the better,” Tracy said.

Soon after the most recent hurricane, our organization and other USACC member organizations sent a letter of support and concern to the Cuban people through Cuba’s ambassador. We wrote: “It is at these times when humanity stands together both in fear of the destructive forces of nature that impact us all, and in solidarity in the determination to help one another recover.”

In that spirit, we stand with U.S. wheat farmers to support ending the Cuban embargo entirely.