By Steve Mercer, USW Vice President of Communications

Two recent market articles by Reuters have caught our attention here at U.S. Wheat Associates (USW).

At first glance, the Aug. 20 story “Russian Traders May Speed Up Grain Exports Amid Risks of Curbs,” and the Aug. 22 story “Global Wheat Supply to Crisis Levels; Big China Stocks Won’t Provide Relief” may not seem related. Together, however, they are another caution sign for the world’s wheat buyers.

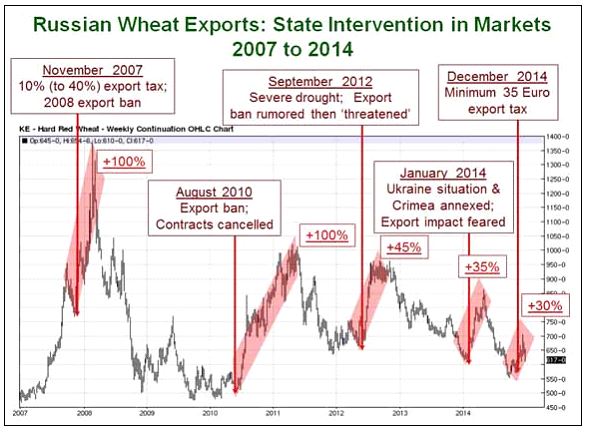

We understand why the Russian traders would want to “speed up” exports if they could: they are afraid of export restrictions. There is plenty of proof that the Russian government is willing to curb overseas sales. Restrictions in 2007/08 helped tip the markets into a supply shock with unprecedented price increases. A complete Russian export ban in 2010 pushed prices higher and showed complete disregard for the sanctity of sales contracts. Two years later when drought again hurt the Russian crop and the government threatened an export ban, global wheat prices moved up. Then when the government imposed an export tax in 2014, the market reacted as expected.

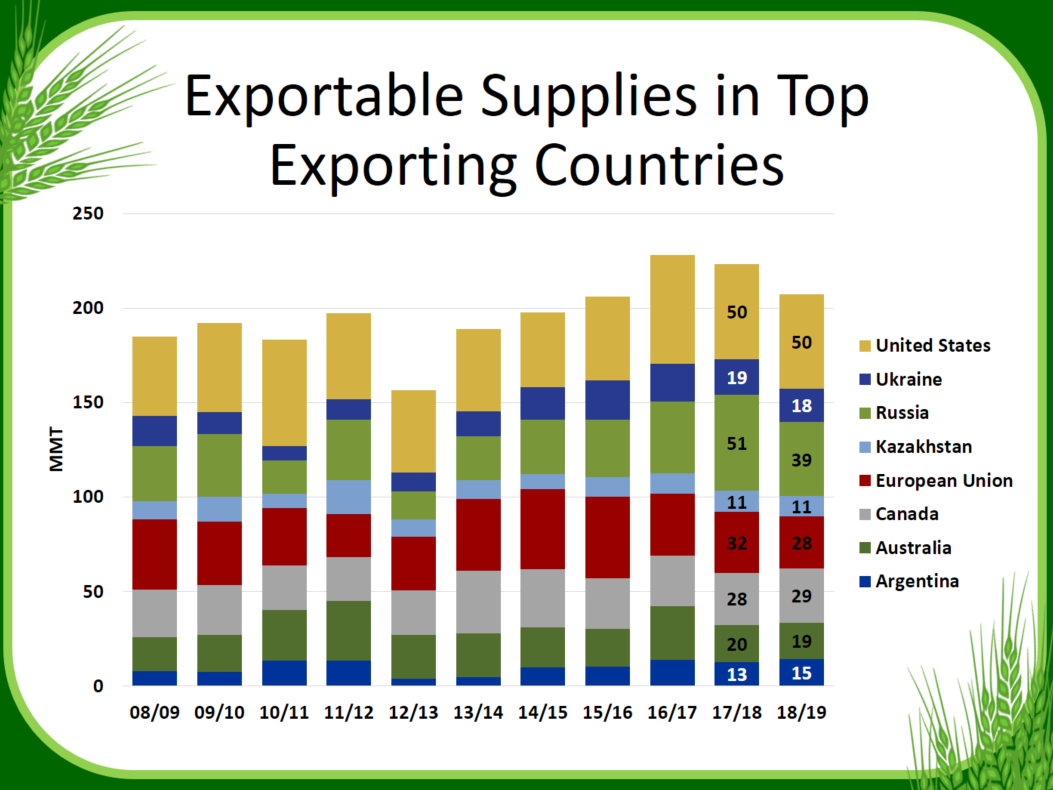

What is quite striking to us, however, is the fact that the possibility of export restrictions has come up again in a year in which Russia has produced its third largest wheat crop.

As an unnamed industry source in the Reuters article said: “When it comes to choosing between meeting food security or curbing exports, they will be choosing (limits on) exports again and again.”

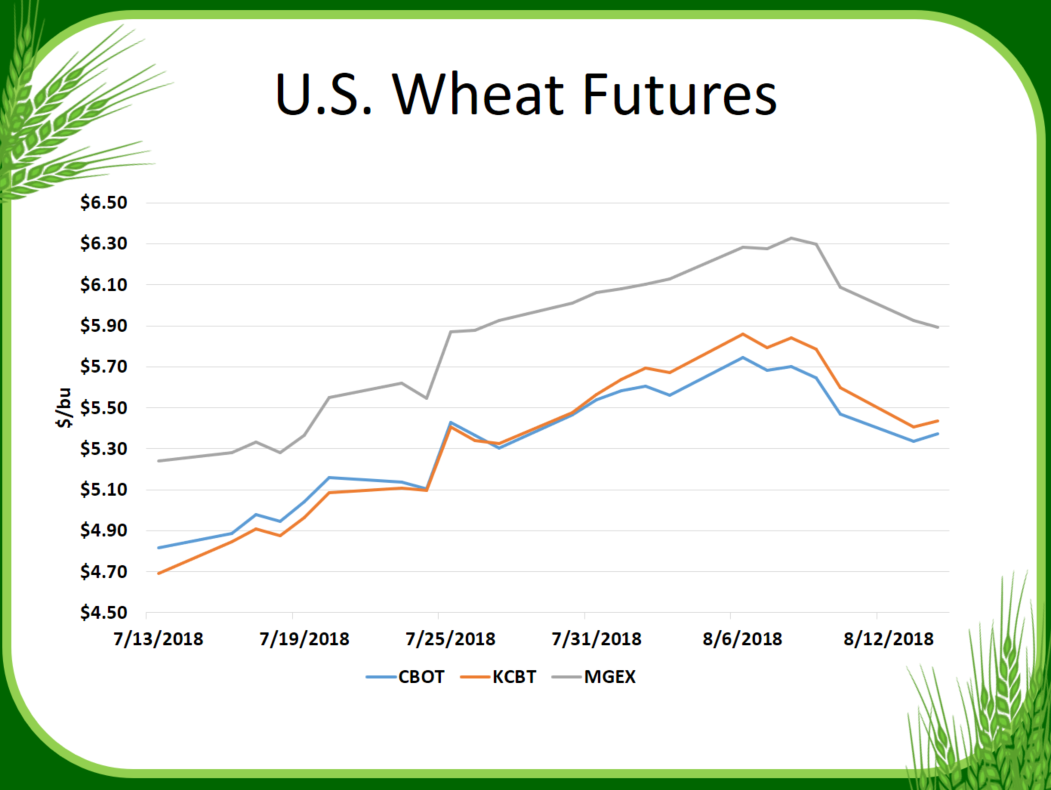

Yes, a Russian government official said, “the introduction of grain export duty is not planned so far.” But we all saw futures prices bounce up quickly when just the subject of Russian restrictions came up last week. We should not forget that prices jumped “limit up” just on an apparently false rumor that Ukraine’s government might restrict wheat exports.

Which brings up the second Reuters article that started this way:

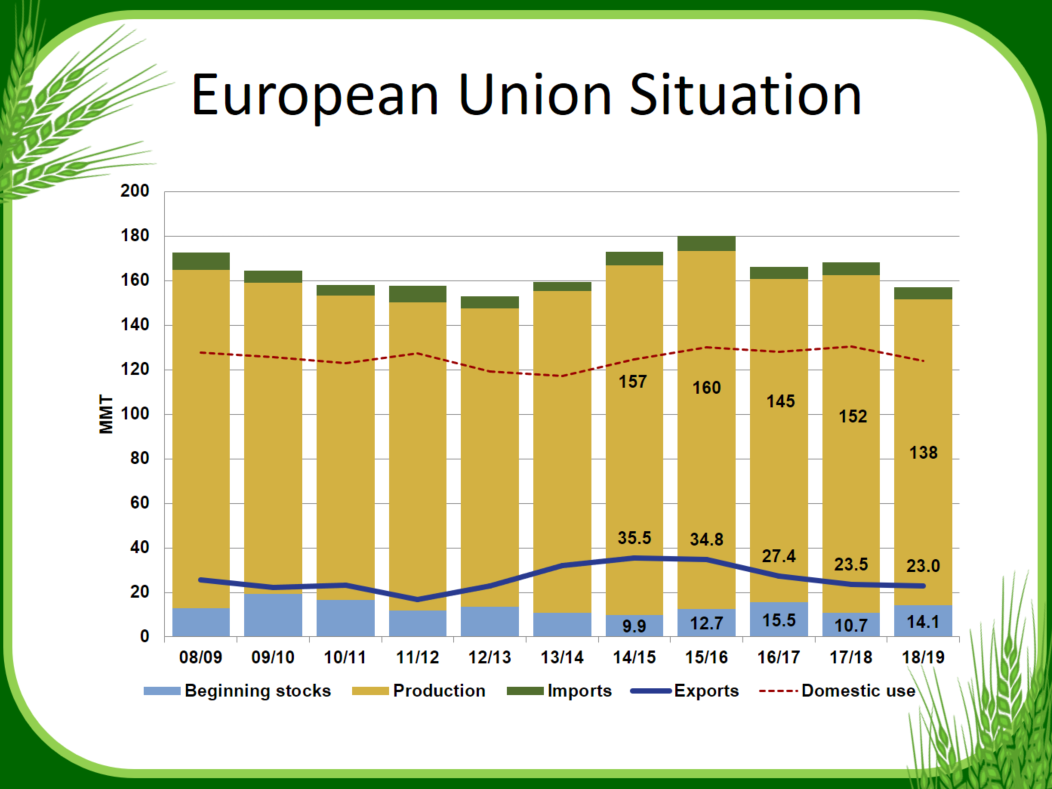

“A scorching hot, dry summer has ended five years of plenty in many wheat producing countries and drawn down the reserves of major exporters to their lowest level since 2007/08, when low grain stocks contributed to food riots across Africa and Asia.”

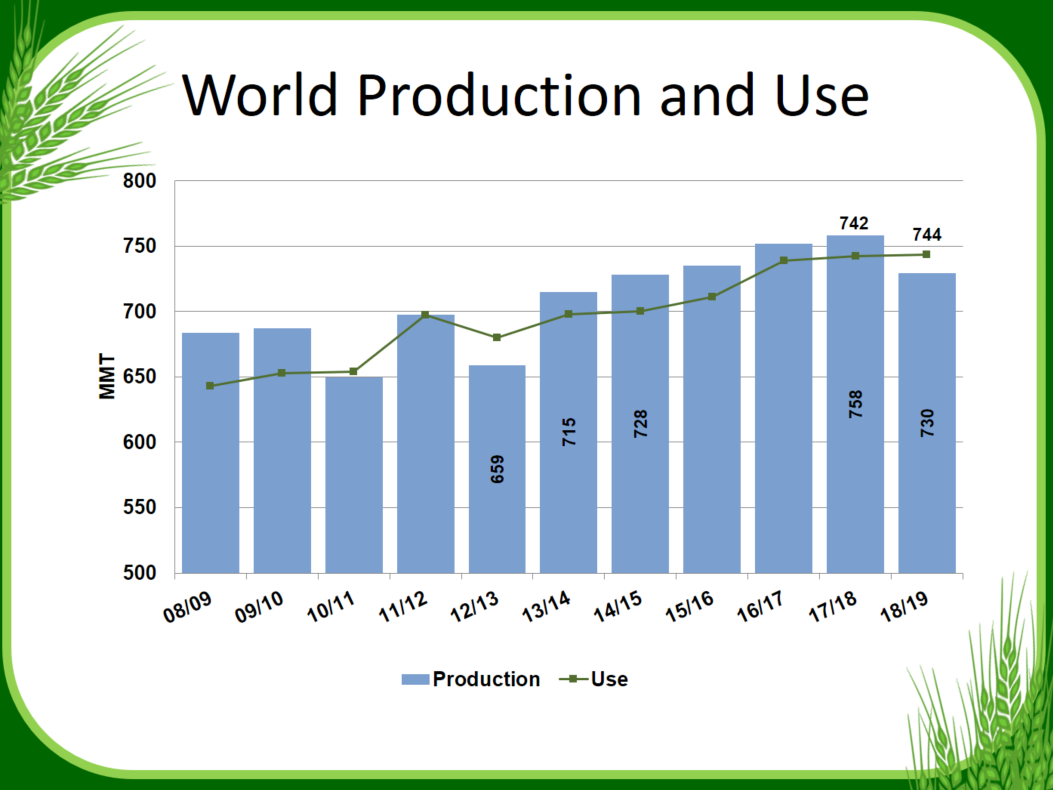

A bit of hyperbole there, perhaps, and the article suggests that there are factors that could mitigate a similar supply shock. Yet, the article noted: “Experts predict that by the end of the season, the eight major exporters will be left with 20 percent of world stocks – just 26 days of cover – down from one-third a decade ago.”

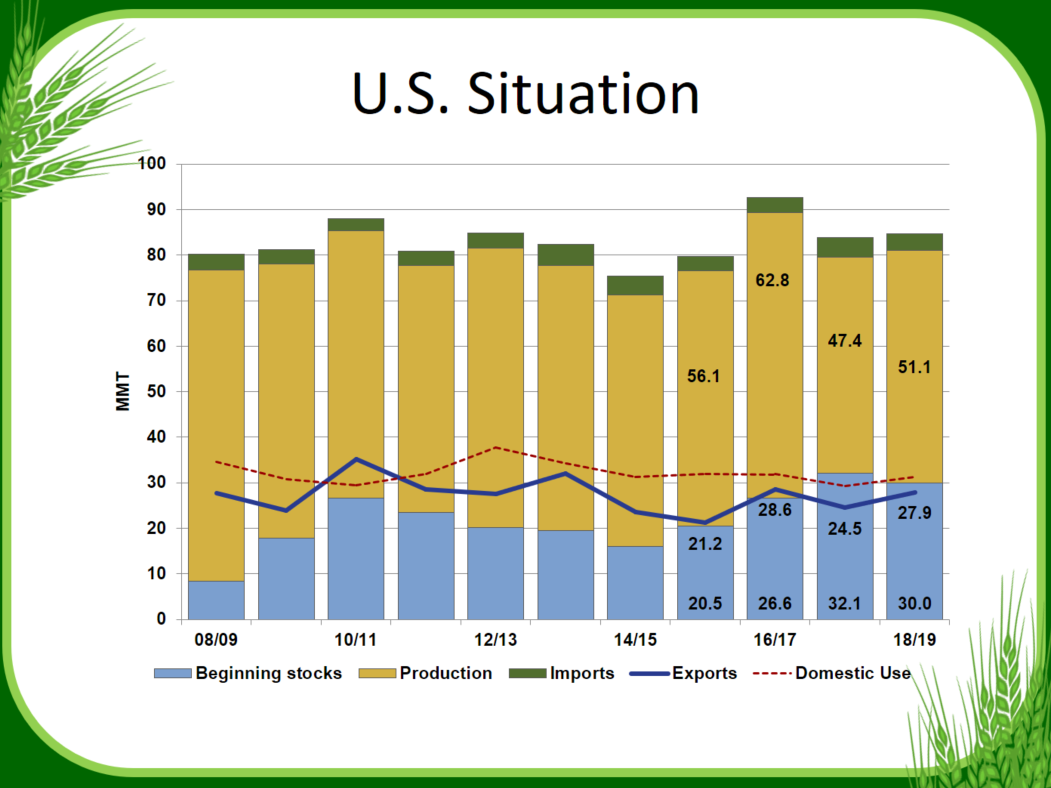

“The world just continues to grow,” said USW President Vince Peterson. “If we check on it, we see that world wheat consumption has grown 100 million metric tons in just the last 10 years. And we’re now at a place that even a very good crop in Russia causes concern.”

There is an old saying that keeping all your eggs in one basket is a risky proposition. Instead, the world’s wheat buyers might consider keeping a more diversified stable of suppliers — ahead of what could be, if not yet “crisis level,” at least a steady rise in global wheat prices.

Fortunately, the U.S. government long ago learned from experience that disrupting export grain trade only brings logistical problems and potential economic catastrophe for every segment of the market, including farmers. By law the only way to block U.S. grain exports is through a presidential declaration of national emergency. Importantly, a national emergency does NOT include short-term, fundamental rises in wheat prices. Further, export taxes are expressly forbidden by the U.S. Constitution.

The U.S. wheat industry offers reassurance in the fact that our doors are open for business 365 days per year. In our collective efforts to offer and efficiently supply the widest range of the highest quality wheat in the world, we live up to our claim as the world’s most reliable supplier.

The Russian government’s past actions prove that even a hint of rising domestic food costs can spark intervention in the free flow of its wheat to an increasingly hungry world.