By Steve Mercer, USW Vice President of Communications

Wheat farmers in post-World War II United States were producing more wheat than ever before. So, to improve marketing opportunities, they organized and reached out to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) for help. These visionary state wheat leaders ultimately formed two regional organizations to coordinate export market development: Western Wheat Associates and Great Plains Wheat Market Development Association.

In the third of a series on the “Legacy of Commitment,” Wheat Letter offers historical perspective on how changes in federal programs, global market factors and relationships drew Western Wheat Associates and Great Plains Wheat ever closer together and led to the establishment of one export market development organization – U.S. Wheat Associates.

“It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent that survives. It is the one that is the most adaptable to change, that lives within the means available and works cooperatively against common threats.” – Charles Darwin

In 1959, foreign currency funds were building in several countries that were buying U.S. wheat under U.S. Public Law 480. The funds could only be used for export market development.

USDA’s Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS) told Great Plains Wheat Market Development Association (GPW) it was time to step up their efforts. And when Western Wheat Associates (WWA) was founded, FAS told its leaders that the agency wanted to move wheat to overseas markets regardless of their potential for becoming cash customers.

“It is interesting to note that FAS, being the banker of market development funds, has had an influence on our internal policies from the very first meeting,” wrote WWA CEO Richard K. Baum in his report The First Twenty Years.

As the history of organized, public-private export market development of U.S. wheat evolved, these three partners would find themselves adapting to many changes and threats at home and abroad. Though the relationships at times were tested – and there was what Baum termed a “healthy and friendly competition” between WWA and GPW – the spirit of cooperation remained strong.

Regional Focus

The formation of regional export promotion organizations by state wheat farmer leaders was a logical outcome of circumstances in the 1950s.

In Kernels and Chaff, A History of Wheat Marketing Development, Marx Koehnke noted that soft red winter (SRW) grown east of the Mississippi River had been the most exported U.S. wheat class because it was more accessible to export points. Overseas buyers were not getting the quality they needed to make bread from SRW. Koehnke also wrote that hard red winter (HRW) grown in the Great Plains and “needed by the foreign buyers” was going into government surplus stockpiles. With support from FAS, GPW was established specifically to promote HRW and hard red spring (HRS) in Europe and Latin America served by Gulf, East Coast and eventually Great Lakes ports.

With soft white (SW) production concentrated in Pacific Northwest states, a region gifted with natural export tributaries, it was logical for WWA to focus on promoting SW in Asian wheat markets. Even as state wheat commissions in Oregon, Washington and Idaho were organizing WWA, however, discussions with GPW leaders revealed an interest in promoting HRW in Asian markets, too.

GPW and WWA signed a Memorandum of Understanding in May 1959 to share expenses equally for export development programs in the PL 480 markets of India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. Koehnke wrote this agreement “was a coordination of joint efforts to expand the total market for U.S. wheat…and was to continue through the years.”

Photo from “Kernels and Chaff; A History of Wheat Market Development.”

Dealing with Resistance

A bit of early resistance to coordinated market development appeared after GPW identified in 1961 the growth of bread and roll consumption in Japan. Even though the higher protein wheat grown in the Plains was needed to meet that demand, Kernels and Chaff indicates that the organization sensed some reluctance on WWA’s part to have GPW participate in the Japanese market. The reasons for this alleged “reluctance” are not recorded, although in hindsight PNW farmers had opened and developed this market and WWA’s leaders may have had strong feelings of ownership.

The spirit of cooperation prevailed and in return for promoting hard wheats in Japan, GPW invited WWA to participate in European and South American market activities to identify potential demand for SW wheat. A committee to help coordinate all wheat export market development activities was also formed with members from WWA, GPW, the domestic export grain trade, and the domestic U.S. milling organization (which was likely selling bread flour to Japan at the time). In addition, WWA gained agreement from GPW to represent the interests of both organizations in Washington, D.C. FAS strongly supported such cooperation – support that, to Baum at least, indicated FAS was “already pushing for a merger of GPW and WWA.”

The cooperation on promoting HRW and HRS in Asia was tested over the next several years because of the cost constraint to move these U.S. classes to ports and to Asian markets. There were proposals by Plains farmer organizations to increase the existing U.S. government subsidy on wheat exported from Gulf ports, and to reduce rail rates on wheat moving from the Plains to West Coast ports. The WWA board of directors opposed these proposals “without similar reductions from states closer to the West Coast.” Ultimately, WWA’s board created a transportation committee that worked out agreeable solutions with GPW.

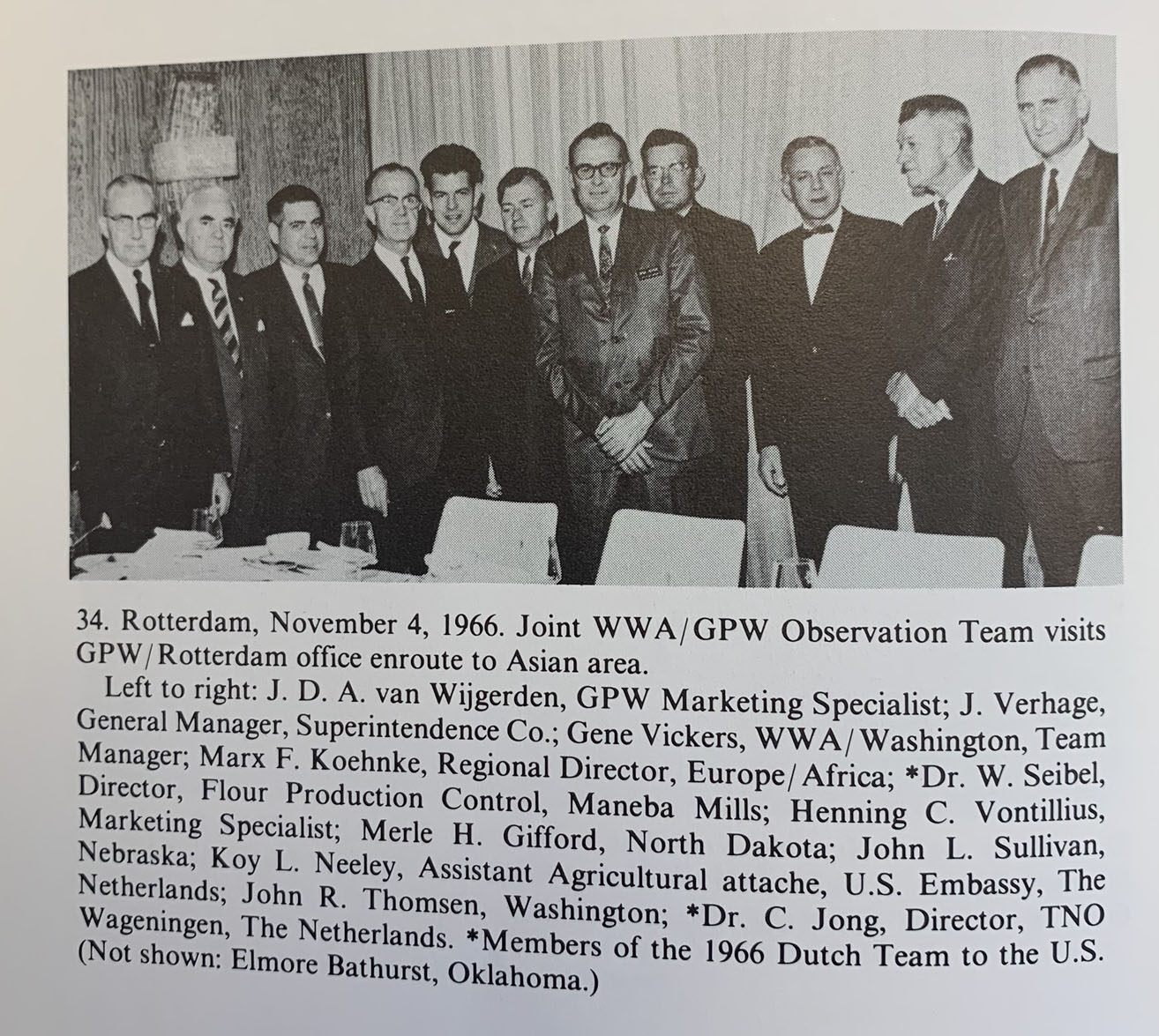

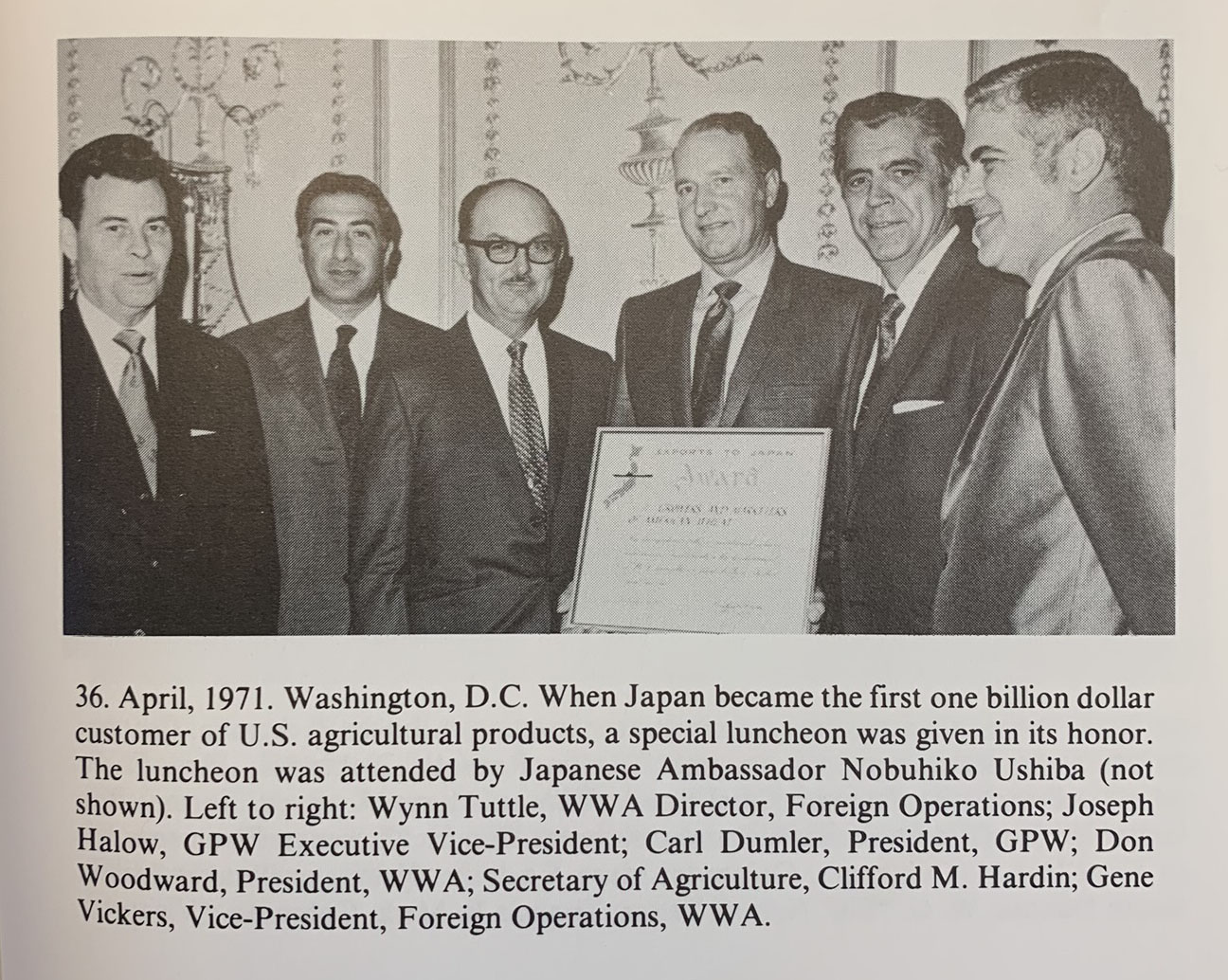

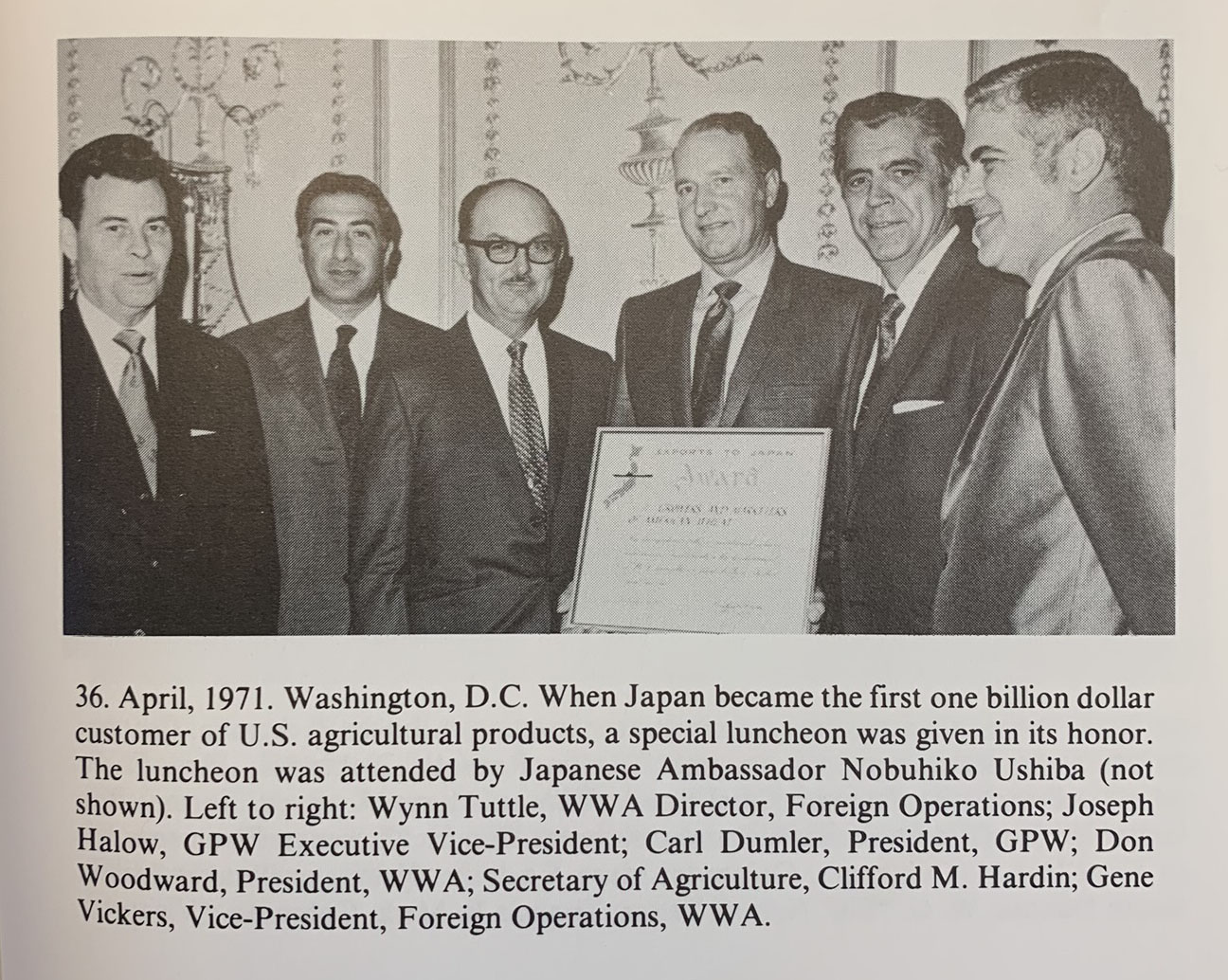

By maintaining frequent contact and coordination, customizing ways to represent all regionally produced wheat in markets designated in their separate marketing agreements with FAS, GPW and WWA developed a steady collaboration. For example, they worked together to try to gain representation at PL 480 planning meetings and International Wheat Agreement negotiating sessions, observing that there was not enough representation from people well-versed in wheat production and trade. Together they also supported FAS in resisting calls from other U.S. farm and business organizations to reduce PL 480 program funding. By 1971, both organizations and USDA were celebrating the fact that Japan was the first overseas customer to import an annual volume of U.S. wheat valued at $1 billion and now including more HRW and HRS than SW .

Photo from “Kernels and Chaff; A History of Wheat Market Development.”

The Waring Report

In the mid-1960s, FAS sponsored a team to evaluate the work of GPW and WWA. Fred Waring, a retired USDA auditor, led the team on visits to Europe, Asia and the Middle East to review specific activities and confer with U.S. ag officials, importers and others engaged in wheat trade. The so-called Waring Report recommended many changes to improve and strengthen market development. In terms of activities, the report suggested that detailed plans with clearly defined and measurable goals, objectives and activities be developed, and recommended emphasizing trade and technical services customized for each market.

In addition, the report suggested that one organization focused on U.S. wheat export development should be developed.

Kernels and Chaff notes that GPW and WWA responded to the evaluation “by agreeing to the general observations and recommendations.” Specific responses are not carefully recorded but in 1965, GPW was surprised to learn that the Nebraska Wheat Commission (NWC) intended to end its membership in the organization and join WWA. Koehnke wrote that NWC cited several issues leading to its decision including “resistance to recommendations in the Waring Report…a tendency to avoid cooperation with WWA…and a perceived belief among GPW staff that FAS gave WWA preferred treatment.”

After GPW reviewed and reorganized its operations, NWC returned to membership in the organization, but maintained its membership with WWA. In some ways NWC’s actions offered the first signs that circumstances in the global wheat market were changing. As new states formed commissions, more of them joined both GPW and WWA, whittling away at regional views of how best to promote the wheat their farmers were growing.

Stronger Together

Once again, there is little specific insight into why the concept of combining U.S. wheat farmer groups into one organization continued to be put forward. In 1967, at a meeting of the National Association of Wheat Growers (NAWG), a committee to study the feasibility of combining NAWG, GPW and WWA was formed. No change was made but it appeared the committee continued to meet. In 1971, Baum and Koehnke recorded that WWA authorized funding to evaluate the merits of merging WWA, GPA and NAWG. Koehnke wrote that of mutual concern to GPW and WWA was pressure from FAS to increase the portion of producer funding for export market development. Looking back, the dramatic effects of the huge U.S. wheat purchases by the Soviet Union probably put merger talks on hold for many years.

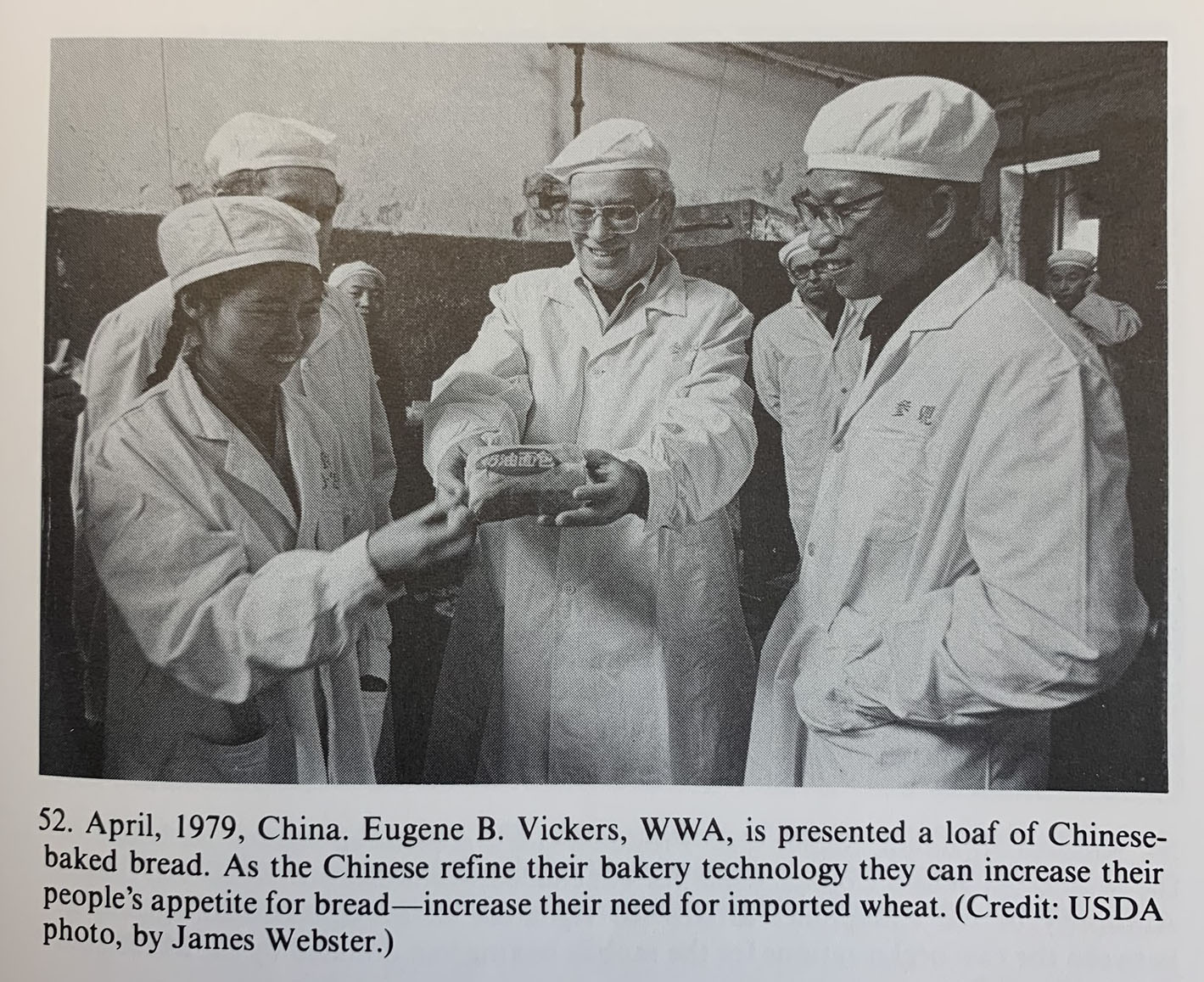

Adjustments to accommodate market factors continued without a merger. In about 1972, WWA assumed all responsibility for promoting all U.S. wheat classes in Asia and GPW assumed the same responsibility for Latin America, Europe, the Middle East and Africa. Separate agreement with FAS continued but this meant that, for example, GPW would bring potential customers on trade team visits to the Pacific Northwest to learn more about SW wheat production and value. The circumstances were drawing GPW and WWA even closer together.

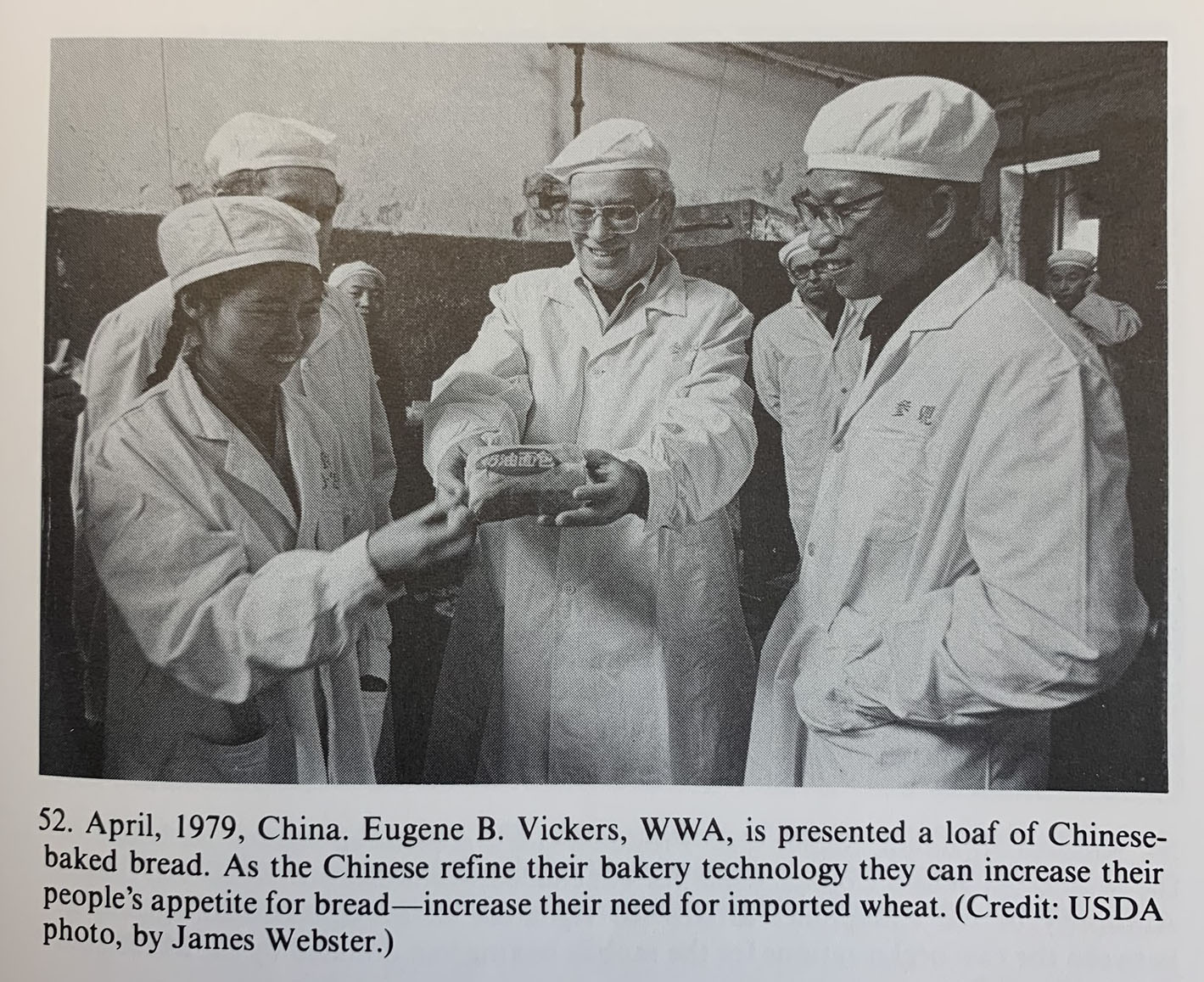

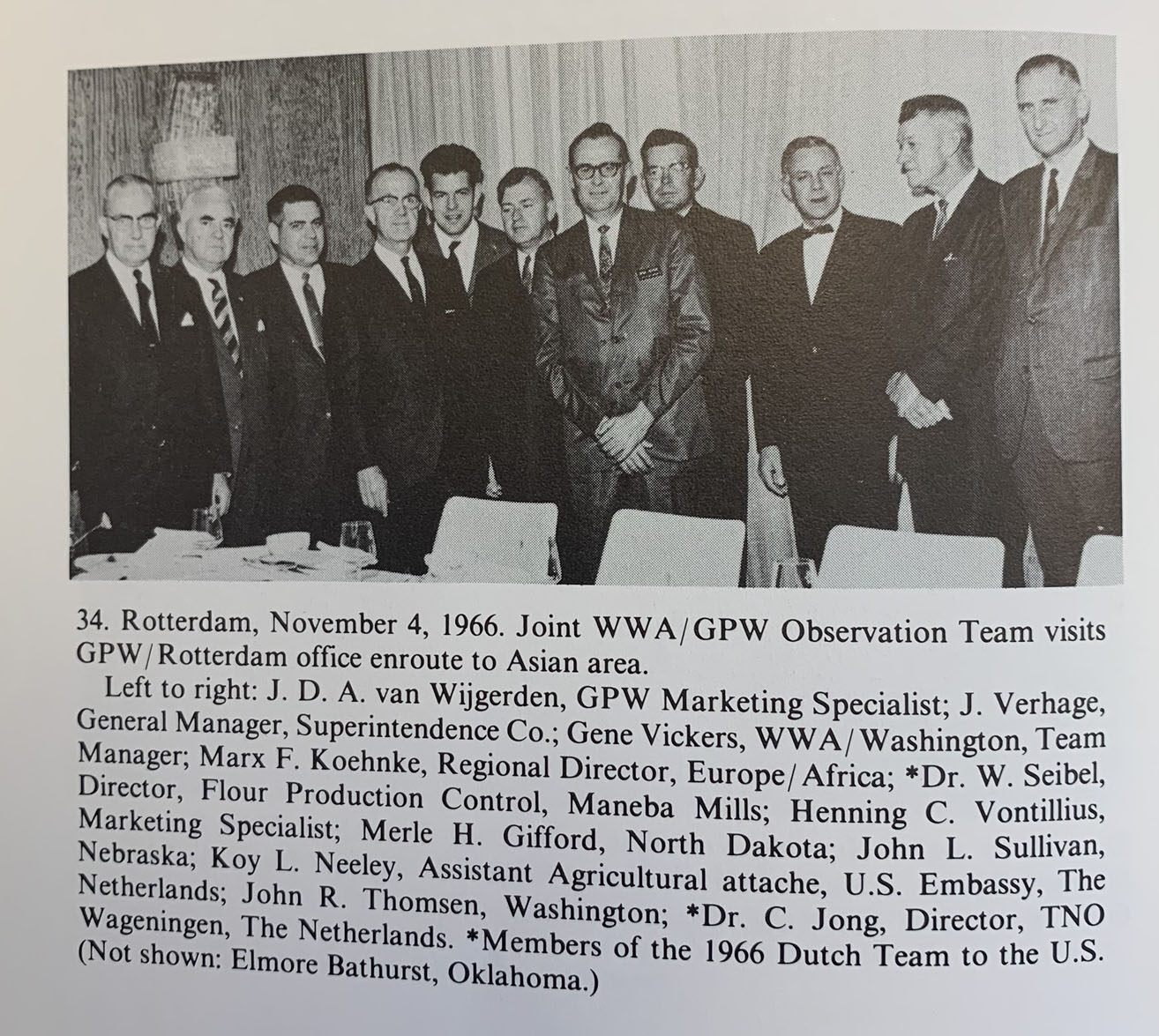

Gene Vickers was a cereal scientist who worked for many years for both WWA and GPW. Photo from “Kernels and Chaff; A History of Wheat Market Development.”

Plans Revived

In Kernels and Chaff, Koehnke wrote that enthusiasm among farmer leaders for a merger of GPW and WWA seemed to grow during 1976. Merger plans and joint committee work were “revived.” In conjunction with NAWG’s annual meeting in Hawaii in January 1977, GPW and WWA held a joint meeting, billed as “Meeting Your Customers Half Way,” that included 220 Japanese executives and representatives from many other Asian countries. At separate discussions during these meetings, the farmer leaders identified several advantages of a merger including “greater efficiency, avoiding duplication of efforts, greater strength in obtaining federal funding, and expansion of markets for all classes of U.S. wheat.”

At this meeting, the name “U.S. Wheat Associates” was first proposed for a merged organization.

It is interesting to note that an FAS representative at the meeting said the agency was “neutral on the proposed merger and the decision was up to the producers themselves.” Funding would be based on the merits of proposed projects, the representative said.

Even as they took the time to take care of their own seasonal farm work, enthusiasm among the farmer leaders for a merger remained. Koehnke wrote that GPW took up discussion of a merger proposal and analysis completed by the North Dakota Wheat Commission in December 1978. At GPW’s January 1979 board meeting, WWA presented its own merger plans. That is when the hard work of making the merger a reality really started.

Wheat Letter has attached Koehnke’s detailed description in Kernels and Chaff of the merger actions in 1979.

One Organization

Recently, former Kansas Secretary of Agriculture and Kansas wheat farmer Adrian Polansky, who represented his state on a merger task force as a first-year Kansas Wheat commissioner in 1979, told High Plains Journal that “combining two distinct entities with differing geographical regions, differing market focuses and completely different structures was a large challenge … but the challenges had to be met.” USDA, from then Secretary of Agriculture Robert Bergland to everyone at FAS, now believed the merger should take place.

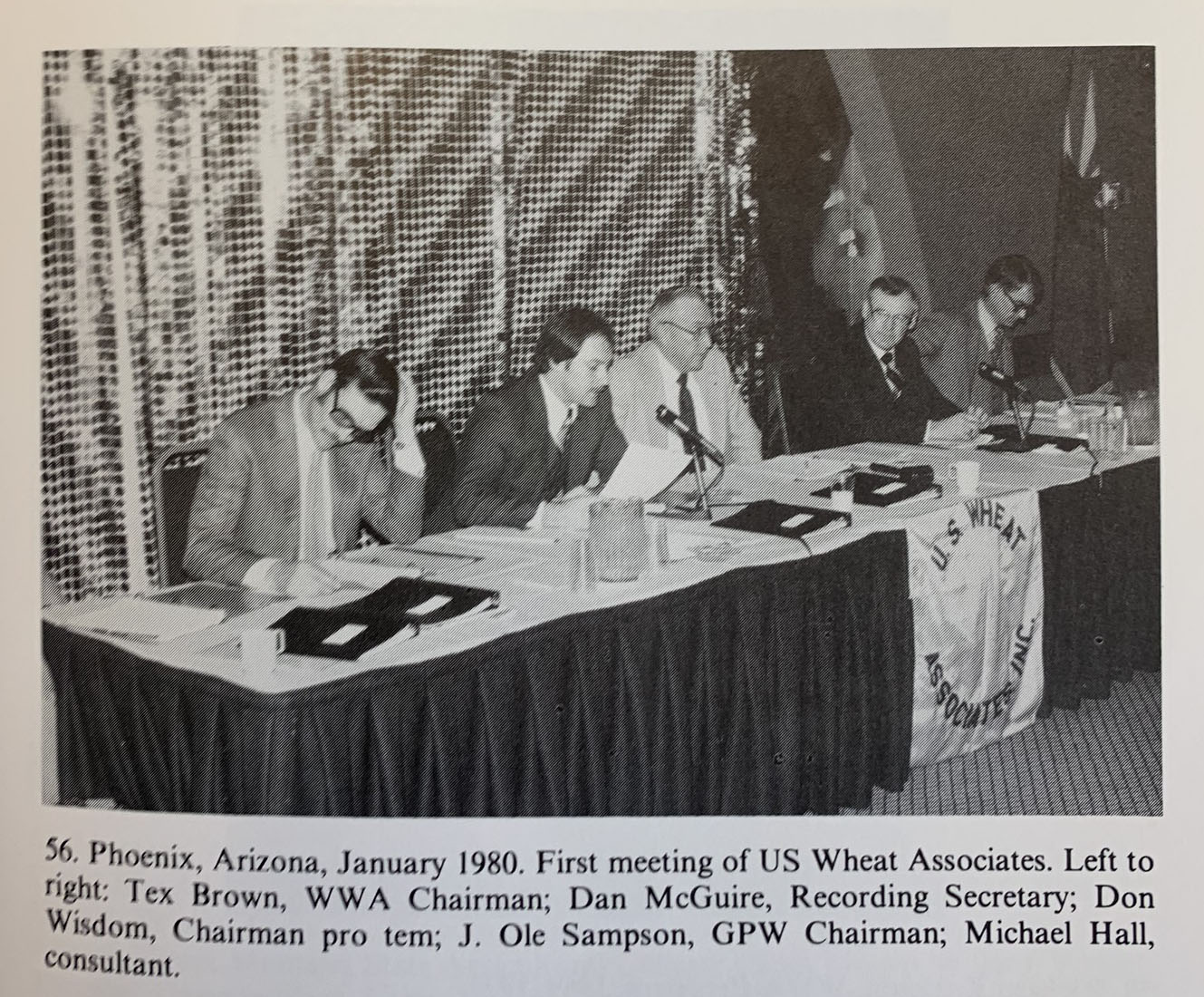

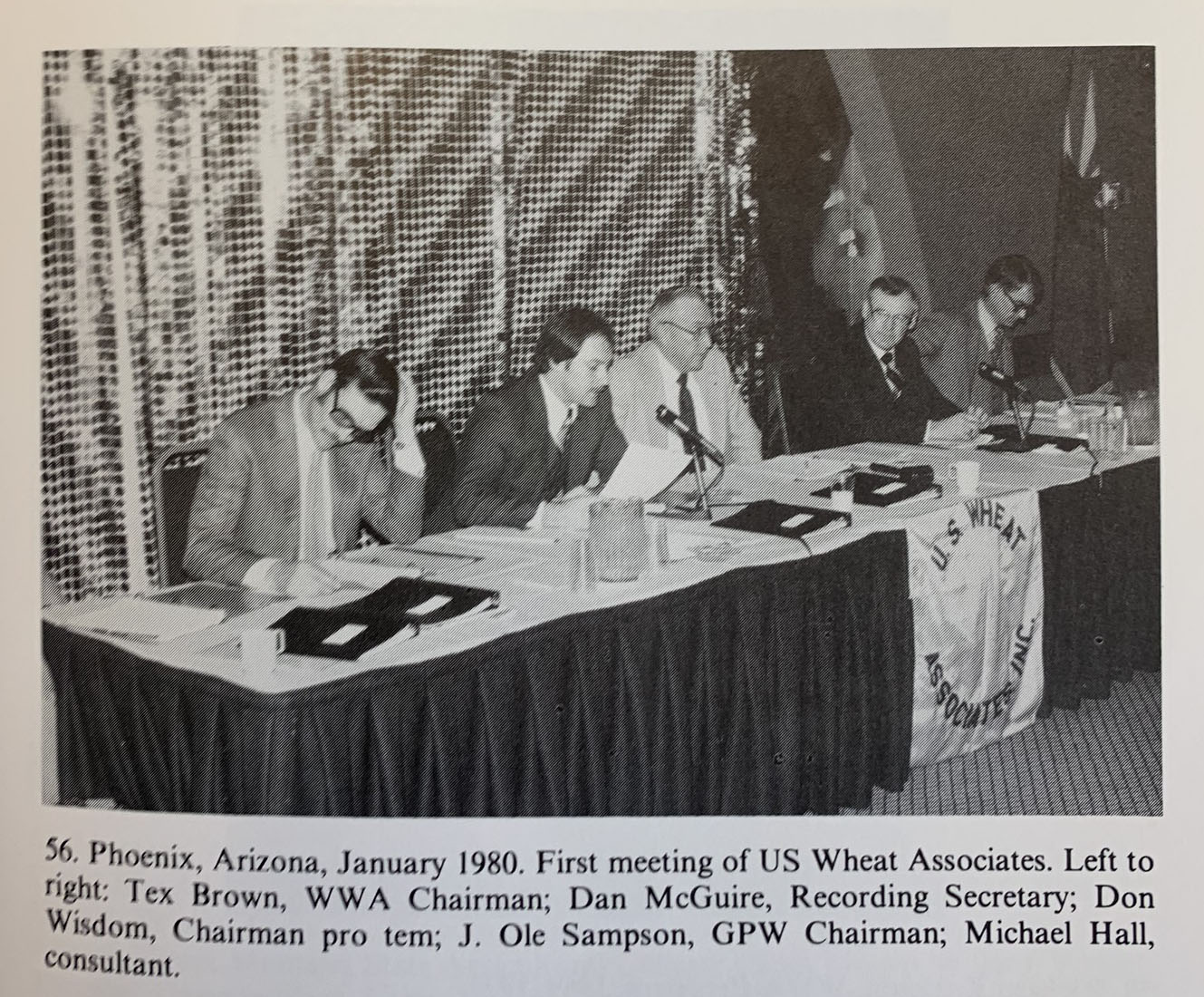

U.S. Wheat Associates was officially formed at a board of directors meeting on Jan. 12, 1980, in Phoenix, Ariz.

Koehnke summarized the 20-year history of Great Plains Wheat and Western Wheat Associates this way:

“Both Dick Baum [WWA CEO] and Mike Hall [GPW President] had built formidable staffs and organizations which were merged into U.S. Wheat Associates. Both [organizations] were highly respected by FAS and the U.S. wheat industry, from producers to exporters, and by the import trade in many countries over the world. Other exporting countries with wheat boards respected the competitiveness of the U.S. wheat [organizations] and emulated their activities in many areas.”

Photo from “Kernels and Chaff; A History of Wheat Market Development.”

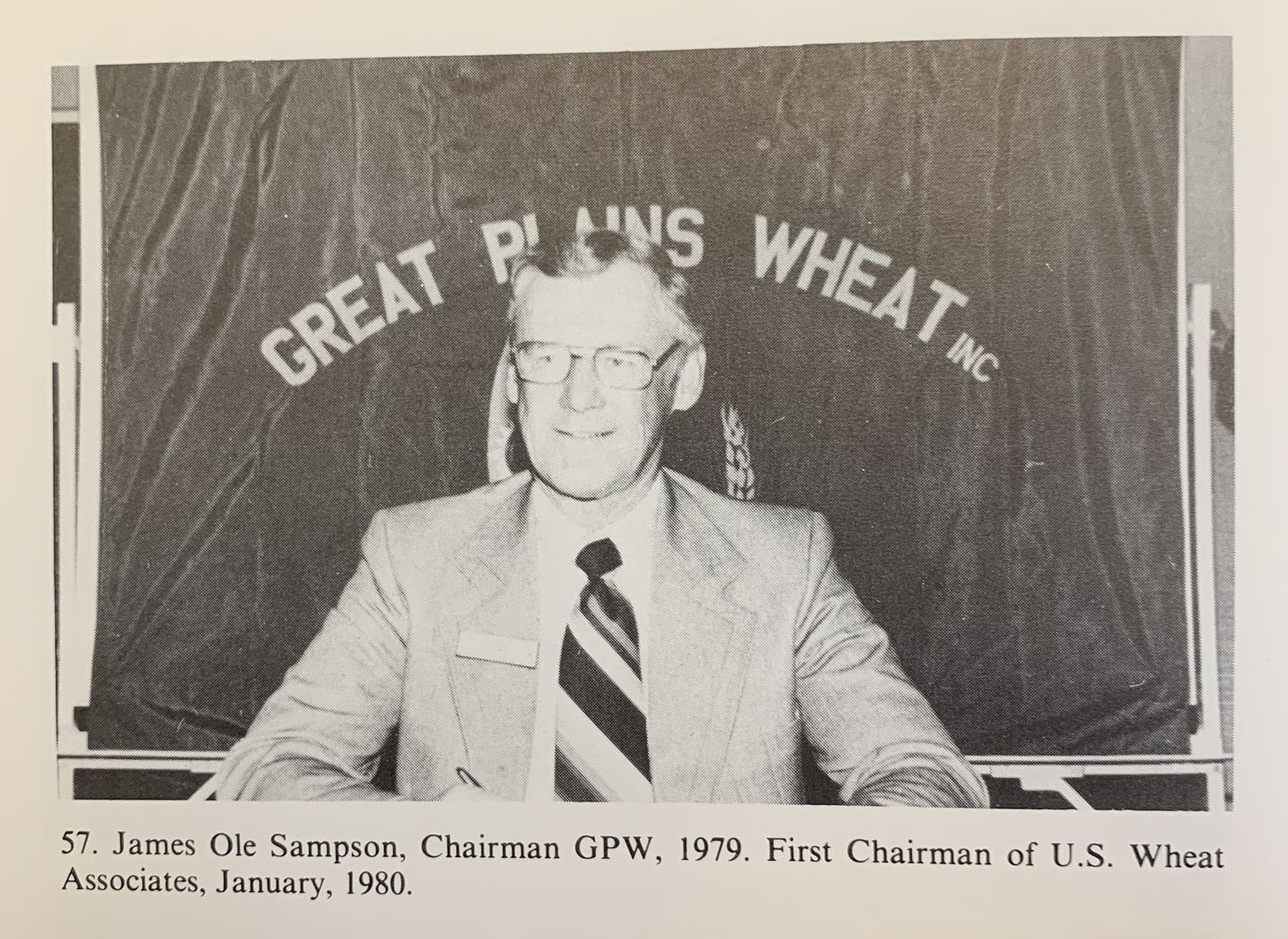

Photo from “Kernels and Chaff; A History of Wheat Market Development.”

###

Sources for this post include:

- Marx Koehnke, Kernels and Chaff, A History of Wheat Marketing Development (self-published, 1986).

- Richard K. Baum, Western Wheat Associates, U.S.A., Inc., The First Twenty Years, 1959 – 1979 (self-published, 1979).

- Jennifer Latzke, Generations of Wheat Farmers Developing Markets: U.S. Wheat Associates Celebrates 40th Anniversary, High Plains Journal, March 13, 2020.

Read other stories in this series:

Western Wheat Associates Develops Asian Markets

Great Plains Wheat Focused on Improving Quality and HRW Markets

The U.S. Wheat Export Public-Private Partnership Today

NAWG, USW Lead the Way Through Issues Affecting Wheat Farmers