Name: Wei-lin Chou

Title: Asian Products and Nutrition Specialist

Office: USW Taipei Office

Providing Service to: Taiwan

Wei-lin Chou will tell you that wheat is the most fascinating food ingredient in the world, but his fascination with food science first started with starches.

“In elementary school, my science teacher showed us an iodine–starch test. In the lab, he dropped iodine reagent on bread and rice. The iodine reagent changed color from brown to purple-blue,” said Chou. “I was so excited about the color changes. I still remember after that class, I started asking many questions about starch and eventually concluded that almost all the foods I love contain starches.”

Life Lessons

Chou grew up in what he says was an ordinary family in New Taipei City, Taiwan. His district, Shulin, translates to “forest” in Mandarin and is famous for red yeast rice and red rice liqueur that is fermented using spores known as “monascus.” This healthy ingredient provides a natural red color and several nutritional functions to various fermented foods. Despite so many childhood memories tied to food, Chou’s parents did not work in the food industry, but his family has strongly influenced how he views the world around him.

“My parents taught me to treat others with honesty and kindness, always feel grateful and cherish the things we have and harm neither others nor our environment,” said Chou. “They taught my sister and me these lessons by living their own lives this way, so my family has really shaped who I am.”

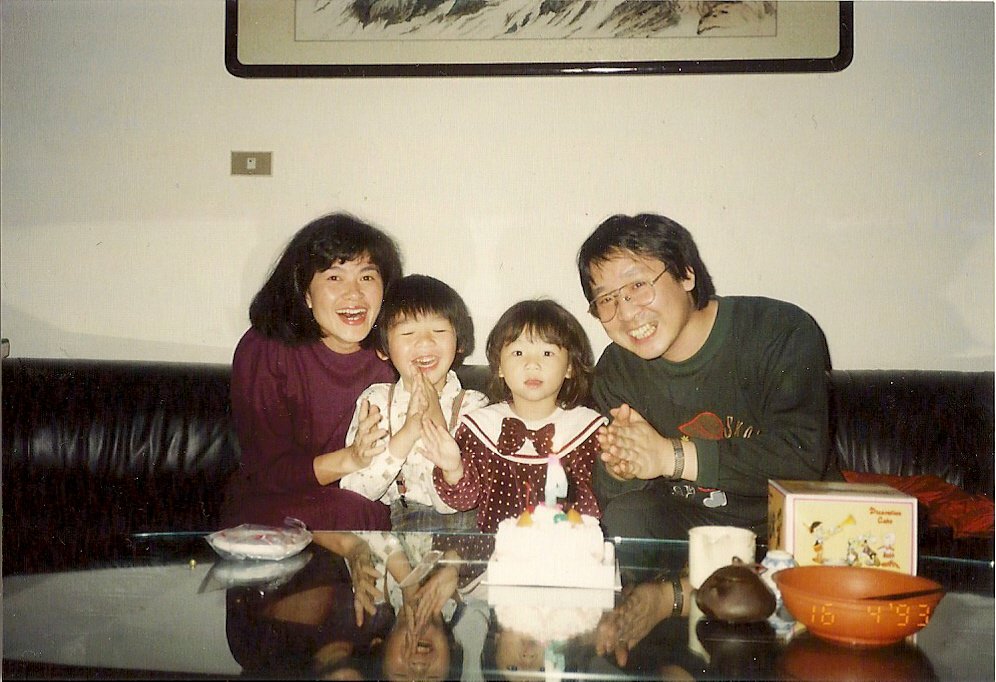

Wei-lin Chou as a kid with his family.

These lessons carried Chou to National Taiwan University (NTU), where he started studying in the nursing department before transitioning to agriculture chemistry. While some might think that is an unusual route to a career in the food industry, Chou believes his experience starting in nursing has helped him further his career.

“Nursing is a career devoted to a human being’s whole life from birth to death, and food is the same. We cannot live without food,” said Chou. “I learned a lot about patience, empathy, respect, communication, and trust-building from nurses. I also learned more about people and their needs at various ages and health situations, whether physical or mental. It now influences the way I support and provide service to customers.”

Building a Career

Once Chou transferred to the agriculture chemistry department, he majored in his true interest – food science. That is where he met his mentor, Dr. Hsi-mei Lai, who emphasized understanding the principles behind testing methods and food processing steps students were applying in their coursework. Chou said he learned from her that collaboration – teaching and sharing with fellow students was the best way to learn. Dr. Lai also regularly took her students to visit food industries and factories, where Chou first experienced interacting with customers and working with them to solve problems.

Wei-lin Chou (third from left) is pictured with his mentor, Dr. Hsi-mei Lai (second from left), who took her student out to visit and interact with food industry customers.

Wei-lin Chou (right) taught gluten qualities to NTU’s Agriculture Chemistry department undergraduate students through the most basic hand washing method in the Food Analysis Lab course.

In addition to earning a bachelor’s and master’s in agriculture chemistry, which included a thesis on rice flour properties and applications, Chou received a scholarship from the Ting Hsin International Group to support his post-graduate work.

After graduating, Chou’s first job was as a research and development assistant at Taiwan’s China Grain Products Research and Development Institute (CGPRDI). Established in 1962, CGPRDI is a historic vocational training, research, and development center for several grain and food products that U.S. Wheat Associates (USW) has supported since 1964 through its legacy organizations.

The USW Taipei Office cooperated with CGPRDI to research what types of bread were suitable for Taiwan’s aging population. Wei-lin Chou produced the bread samples for sensory evaluation in 2020.

“As a fresh graduate, CGPRDI was the most suitable place to put what I had learned to work. Since rice is the major crop in Taiwan, I extended rice flour and starch research to various food applications in CGPRDI,” said Chou. “This work fortified my knowledge of flour and starch and expanded my point of view about the food industry and mass production.”

Next, Chou worked as a technical sales representative for STARPRO Starch Co., reconnecting with the company that provided him with the scholarship in graduate school.

“I love to have adventures and try new things. This was my first time living and working in a foreign country, first in China for a few months and then Thailand for three and a half years,” said Chou.

Wei-lin Chou in a tapioca field when he worked at STARPRO Starch Co.

This work took Chou to several new places, primarily focused on providing service to customers in Japan, Southeast Asia, and Europe. He recalls what he learned from the occasional culture shock and how to communicate better and find common ground with his customers.

“I gained a lot from customers with different views that I might have otherwise ignored,” said Chou. “The international experience also taught me to respect differences and that we cannot judge things only from one aspect.”

Working with Wheat

When Chou heard about the opening in the USW Taipei Office, he said he submitted his resume without any hesitation. It was a new opportunity to work with a food ingredient that fascinated him.

“It is distinctive that U.S. wheat has developed six wheat classes for the various wheat products created,” said Chou. “For me, each wheat product is like a harmonious symphony composed of starches and glutens, so beautiful and kaleidoscopic.”

Unfortunately, Chou started with USW in 2020 after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, which limited travel and in-person activities. Still, Chou has engaged in important research to support a developed market where demand for healthy wheat food products is increasing, especially in schools and Taiwan’s aging population.

Wei-lin Chou conducting a series of solvent retention capacity (SRC) tests in 2021.

“To attempt servicing an advanced market like Taiwan, we need to stay abreast of the latest research in wheat processing and food science, or indeed, to undertake it ourselves. Wei-lin’s background gives him the technical tools to ask the right questions, interpret what is out there for our customers, and make original contributions,” said Jeff Coey, USW Regional Vice President for China and Taiwan. “The work is never done, so to bring younger talent into our wheat world is the future of our program.”

While the pandemic has created limitations, Chou has still been able to make meaningful connections with customers.

“As with my previous work, I really enjoy interacting with customers. After our 2021 Crop Quality Seminars [a hybrid event with pre-recorded videos], many local millers, cooperators, and customers contacted me wanting to learn more about starch and pasting properties,” said Chou. “It felt great to be able to provide that technical support and help build on their needs step by step.”

USW staff at a core competency training in 2022. (L to R) Ady Redondo, USW Manila; David Oh, USW Seoul; Roy Chung, USW Singapore; Mark Fowler, USW Headquarters; Marcelo Mitre, USW Mexico City; Joe Bippert, USW Manila; and Wei-lin Chou, USW Taipei.

Chou has also connected with many of his USW colleagues from around the world who were able to gather in March 2022 in the United States for internal training focused on key core competencies.

“USW has so many awesome technical experts with specialties in milling, baking, and more,” said Chou. “It was so nice to get acquainted with so many colleagues and cooperators. They are all passionate about their work and happy to share their experiences. I enjoy working and interacting with these dependable people.”

Seeking Harmony

In all aspects of his life, Chou is drawn to the things that bring him a sense of harmony and the things that fascinate him, like the colors from the iodine-starch test and the versatility of wheat as a food ingredient. He sees a synergy between those things and his love for music which he says continues to teach him about teamwork and what brings people together.

Wei-lin Chou was a percussionist in his high school marching band.

“I grew up playing in my high school marching band, and that is a group where every member is important and must be fully coordinated. If any member fails in the performance, the music and the formation will be a mess. The team members need to help each other and grow together,” said Chou. “Everyone sometimes needs to sacrifice a little bit to achieve a greater goal. We, technologists, do the same—we are the bridge that connects customers and suppliers to U.S. wheat. That is what makes U.S. wheat so reliable.”

By Amanda J. Spoo, USW Director of Communications

Editor’s Note: This is the tenth in a series of posts profiling U.S. Wheat Associates (USW) technical experts in flour milling and wheat foods production. USW Vice President of Global Technical Services Mark Fowler says technical support to overseas customers is an essential part of export market development for U.S. wheat. “Technical support adds differential value to the reliable supply of U.S. wheat,” Fowler says. “Our customers must constantly improve their products in an increasingly competitive environment. We can help them compete by demonstrating the advantages of using the right U.S. wheat class or blend of classes to produce the wide variety of wheat-based foods the world’s consumers demand.”

Meet the other USW Technical Experts in this blog series:

Ting Liu – Opening Doors in a Naturally Winning Way

Shin Hak “David” Oh – Expertise Fermented in Korean Food Culture

Tarik Gahi – ‘For a Piece of Bread, Son’

Gerry Mendoza – Born to Teach and Share His Love for Baking

Marcelo Mitre – A Love of Food and Technology that Bakes in Value and Loyalty

Peter Lloyd – International Man of Milling

Ivan Goh – An Energetic Individual Born to the Food Industry

Adrian Redondo – Inspired to Help by Hard Work and a Hero

Andrés Saturno – A Family Legacy of Milling Innovation